"I received the football in the pit of my stomach."

"I received the football in the pit of my stomach."

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 102, May 21, 1892

Author: Various

Release Date: January 14, 2005 [eBook #14695]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI, VOL. 102, MAY 21, 1892***

"She-Pantaloons? seedy? Now, do we look like it?"

The speaker was a tall, robust maiden with fair hair; on her knee was an edition (without notes) of the Anabasis of Xenophon, and by her side was Liddell and Scott's Lexicon, in which she had just been tracking an exceptionally difficult—but, let me hasten to add, a perfectly regular—Greek verb to its lair. There were a considerable number of roseate specimens of English womanhood in the library of Girnham College, where, with some natural diffidence, I had ventured to put the rather delicate question to which I received the above reply.

For I had been much troubled in my soul about Sir JAMES CRICHTON BROWNE's recent deliverances with regard to the injurious physical effect of the Higher Education upon women, and, as a devoted—if hitherto unappreciated—admirer of the Fair Sex, I felt I had a theoretical interest in the question, and was bound to verify Dr. BROWNE's views. The most obvious way of satisfying my anxiety was to go to Girnham myself and ask the lady students what they thought about it, and so I did.

"I quite agree," I said, mildly, as I unwound my comforter, "that your course of studies seems to suit you remarkably well. Quite a bevy of female admirable CRICHT—!"

The effect was immediate; an unmistakable rush of lexicons—or were they Todhunters?—hurtled around my devoted head from the fair hands of disturbed and ruffled girlhood.

"Pray don't mention that person again!" said my fair-haired interlocutor, and I thought I wouldn't.

"Well, but," I began, with heroic daring, as I laid aside my respirator, "as to weak chests now?"

I was interrupted by a paroxysm of coughing, which I tried to explain, as my young friends thumped my back with unnecessary zeal, was, owing to my having imprudently ventured out without my chest-protector. As soon as I was able, I feebly hazarded the suggestion that, for growing girls, the habit of stooping over their books seemed calculated to induce weakness in the lungs—but their roars of merriment at the idea instantly convinced me that any uneasiness on this score was entirely superfluous.

"You certainly all look remarkably well," I observed, genially, "particularly sunburnt and brow—"

Here there was a roar of quite another kind. I endeavoured to protest, as I got behind an arm-chair and dodged a Differential Calculus and a large glass inkstand, that I hadn't meant to allude to the obnoxious Physician at all, but had merely intended to convey my hearty admir—

"I know what you're going to say!" interrupted the fair-haired girl, vivaciously. "And you had better not."

As she spoke, she raised me from my seat by the coat-collar with no apparent effort, and deposited me on the top of a tall bookcase, from which I found myself compelled to prosecute my inquiries.

"Nature has been very bountiful to you—very much so, I am sure," I murmured, blinking amiably down upon them through the spectacles I wear to correct a slight tendency to strabismus. "Still, don't you—er—find that your eyes—"

I got no further; I thought some of them would have died!

"How about the effect of learning on your looks, now?" I next inquired. "Is it true that classical and mathematical pursuits are apt to exercise a disfiguring effect? Not that, with such blooming faces as I see around me—er—if you will allow me to say so—"

But they wouldn't; on the contrary, I was given to understand, somewhat plainly, that compliments were perhaps ill-advised in that gathering.

"Are you—hem—fond of athletics?" was the question I put next from my lofty perch. "Do you go in for games at all, now?"

"Of course we do!" said the fair-haired girl, affording a practical demonstration of the fact by taking me down and proceeding with her lively companions to engage in the old classical game of pila or σφαιριστικη, the recreation in which Ulysses long ago found Nausicaa engaged with her maidens. On this occasion, however, I represented the pila, or ball, and although, in justice to their accuracy of eye and hand, I am bound to admit that I was seldom allowed to touch the ground as I sped swiftly from one to the other, still I felt considerable relief when, on my urgent protestations that I was fully convinced of their proficiency in this amusement, they were prevailed upon to bring this pastime to a close.

"We are breaking the rule of silence in this room," said the fair-haired one. "And you do ask such a lot of questions! But, as you seem curious about our athletic pursuits, come and I will try to show you."

I crawled after my guide without a word, inwardly reflecting that I was sorry I had spoken, and heartily cursing (though without pronouncing it aloud) the very name of that eminent Physician, Dr. CRICHTON BROWNE. She took me first of all to a field where a bevy of maidens were engaged in a game of hockey.

"We are keen on hockey," said my guide, and, as she spoke, a girl, flushed and radiant, caught me across the most sensitive part of the shin with a hockey-stick. No need to ask her if she felt well. I limped away, and, in another part of the field, saw a comely and robust maiden practising drop-kicks, utterly regardless of the fact that I was looking on. I received the football in the pit of my stomach, and the name of CRICHTON BROWNE died on my lips.

My guide smiled as she saw that I had taken in the scene that was being enacted under my very nose.

"Do you play cricket?" she asked, with something like pity in her eyes. I did not—but I was by this time in such condign fear of this young Amazon that I was really afraid to admit my total ignorance of the sport. She made me wicket-keep for her, without pads, for an entire hour, at the end of which I readily assented to an invitation for further exploration.

We went through endless passages to an endless gymnasium, and every now and then I came across an Indian club or a dumb-bell, wielded by energetic female athletes. I should have liked to ask them whether they felt well, but I realised—only just in time—that the question would have been an impertinence.

"Are you getting satisfied?" said my unwearied guide, with another of her smiles, "or, do you still think we are a puny misshapen race?"

"Quite satisfied!" I replied, faintly, as I endeavoured to unclose a rapidly discolouring eye, "in fact, I begin to discredit that alarmist cry—"

Before I could complete the sentence, I found myself executing an involuntary parabola over some adjacent parallel bars. My young friend's brows had contracted into a frown, although she waited politely for me to pick myself up.

"I thought we agreed not to mention that name!" she said, coldly.

I felt that any attempt to explain my innocence would be received with quiet scorn. "I—I should like to ask you just one thing more," I said, desperately, as I lay on my back, "I am really entirely converted—quite ashamed. I do hope you won't think me—er—inquisitive—but I have been so often told—it has been so constantly asserted—" I found myself bungling horribly in my desire not to offend.

"Pray go on," she said, "we try to be simple and sincere, and we are always ready to satisfy an intelligent inquirer."

"Well," I said, desperately, "people do say that you all wear—er—blue stockings. But I am sure," I added quickly, "that it is not true" ...

It was too late. When the friend who had smuggled me into the building came to my rescue, he asked me, rather noisily, "if I was feeling well?" I replied that I was not, and that I did not think I ever should again. And I never have.

[A West-end hosier advertises suits of Pyjamas in his window as "the latest styles in slumber-wear."]

All hail, O hosier; deem me not absurd

That I should thank thee for so apt a word.

'Tis thus that Modesty our language trims:

Where men say "legs" she softly whispers "limbs."

And, while they fume and rage in angry pother,

Stills the big D—— and substitutes a "bother."

Speaks not of "trousers"—that were sin and shame;

"Continuations" is the gentler name.

Turns "shirts" to "shifts," and, blushing like the rose,

Converts the lowly stocking into "hose."

Thus thou, my hosier, profferest me a pair

Of these, the latest style of slumber-wear.

Miss Certainage (who has been studying Schopenhauer, and has come to the conclusion that there is nothing but sorrow in life, sadly). "AH, MAJOR, I'M SURE I SHALL DIE YOUNG!"

Ethel. "OH NO, AUNT DEAR, I'M CERTAIN YOU WON'T!"

Oh where, oh where is my little wee fund?

Oh where, oh where can it be?

With the pence cut short and the pounds cut long;

Oh where, oh where can it be?

I've travelled about with my little wee fund—

It used to pay for me;

But now it's gone I'm lorn and lone;

Oh where, oh where can it be?

I want to stump through Switzerland;

On the 24th proximo.

To Germany, Sweden, Norway, and

To Denmark I want to go;

I've held out my hat to every flat,

And begged over land and sea,

Humanity dunned, but I have no fund—

Oh where, oh where can it be?

If ever you see a stray bawbee

Whenever, wherever you roam,

Oh, tell him the woe that troubles me so,

And say that it keeps me at home.

I may mention that what you do, like a shot

Must be done to be useful to me;

At once send a cheque to save us from wreck,

Or the Army will go to the D!

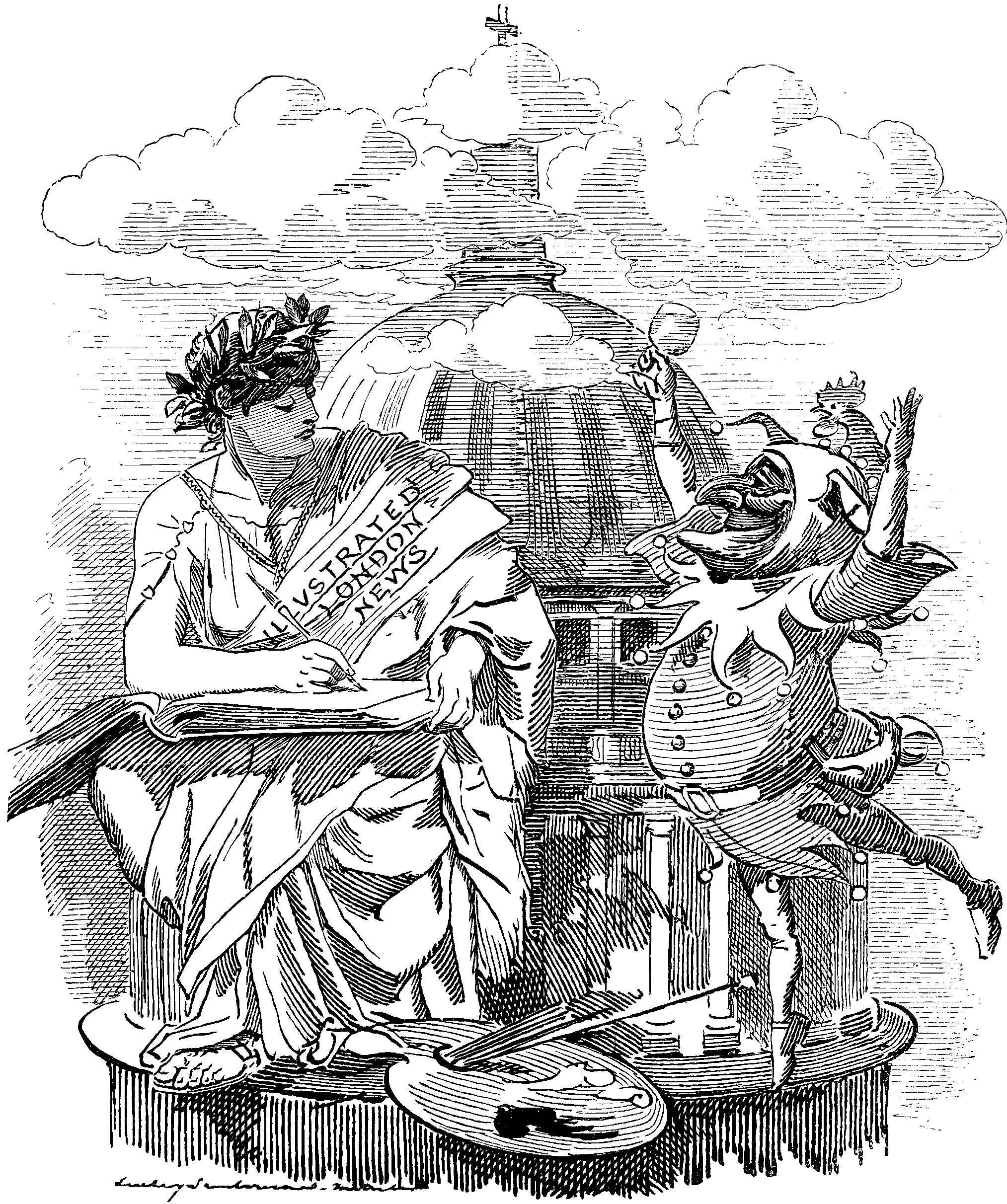

From Forty-Two to Ninety-Two!

A full half-century of story!

And now, our Century's end in view.

May's back once more in vernal glory,

And with it brings your Jubilee,

(Punch came to his one year before you!)

"Many Returns," Ma'am, may you see,

And honoured be the hour that bore you!

Good faith! it scarcely seems so long

To us old boys, who can remember

The tale, the picture, and the song

We pored o'er by the wintry ember;

And how our young and eager eyes

Were kept from childhood's easy slumbers

By the awakening ecstasies

Of cheery coloured Christmas Numbers.

We loved great GILBERT, Glorious JOHN!—

Sir JOHN to-day, good knight, fine painter!

Our eyes dwelt lingeringly upon

His work, by which all else showed fainter.

His dashing pencil "go" could give

To simplest scene; a wondrous gift 'tis!

How his bold line could make things live

In those far Forties and old Fifties!

And humorous "PHIZ" and spectral READ,

Made us alternate smile and shiver.

Ah! ghosts, Ma'am, then were ghosts indeed,

Born of the brain and not the liver.

You shared our LEMON and our LEECH;

Our BROOKS for you ran bright and sunny.

May you live long, to limn and teach.

Be graphic, genial, sage, and funny!

We like you well, we owe you much,

True record, blent with critic strictures,

And culture of the artist touch

Through half a century of pictures.

We wish you many gay returns

Of this May day! You're brighter, plumper

Than then; and Punch, who envy spurns,

Drinks your Good Health, Ma'am, in a bumper!

"ORME! SWEET ORME!"—Orme is still off solid food, and is kept alive entirely by Porter. It is the opinion of the best informed that "Porter with a head on" will pull him through. Smoking is not permitted in the stable, but there is evidence of there being several "strong backers" about.

Mr. John Hare, Lessee of the Garrick Theatre, in his evidence before the Theatres and Music Halls Committee, described himself, according to the Times Report, as having "been for about thirty years an actor, and for fifteen years a manager." This gives him forty-five years of professional life, and saying, for example, that he commenced his career as an actor at twenty, then his own computation brings him up to sixty-five If this be so, then Mr. JOHN HARE, with his elastic step, his twinkling eye, his clear enunciation, and his energetic style, is the youngest sexagenarian to be met with on or off the stage; and it is probable that when he reaches the Gladstonian age he will be more sprightly than even the Grand One himself.

In answer to a question put by Viscount EBRINGTON, Mr. EDWARD TERRY gave it as his opinion that "if officers"—he was speaking of the army not the police—"were prouder of their uniforms, and did not take the earliest opportunity of divesting themselves of them, the uniform would be more respected." He ought to have put it, "would be uniformly more respected." But how about the man inside the uniform? But why should a soldier wear his uniform when off duty any more than a policeman when off duty, or any more than a barrister should wear his wig, bands, and gown, when not practising in the Courts? There is one person who should always wear a distinctive uniform, and that is a Clergyman, who is never off duty. Perhaps this is already provided for by the Act of Uniformity.

Mr. JOHN HOLLINGSHEAD, after expressing his opinion that Mr. IRVING had been "seeing visions,"—which of course is quite an Irvingite characteristic,—proposed to put everything right everywhere, and be the Universal Legislator and Official Representative of Everybody. Salary not so much an object as a comfortable home, a recognised official position, and "No Fees." (The Commission still sitting may perhaps dissolve itself, and appoint the last witness as Sole Theatrical and Music Hall Commissioner, with no power to add to his number.)

House of Commons, Monday, May 9.—House dealt with just now after manner of Horticultural Exhibition at Earl's Court. Laid out as three acres, through which JESSE COLLINGS might be expected to lead the cow. But, as SQUIRE OF MALWOOD (a great authority on stock matters) says, the esteemed quadruped is dead, abandoned by its protector at time of disruption of Liberal Party. Exists now only in the form of carcass, to be found rather in butchers' shops than on quiet pastures. Pity, this. Difficult to imagine any better arrangement for what theatrical people call "properties" than the cow—probably with a blue ribbon round its neck—led through three acres of green meadow by JESSE COLLINGS, in clean smock-frock, with a crook in his hand.

Dr. CLARK says they don't drive cattle with crooks. But that's a detail. CLARK sure to contradict in any case.

Things very quiet to-night; quite pastoral. Only one outburst; that arose when FOSTER accused CHAMBERLAIN of saying the thing that is not. CHAMBERLAIN hotly rose, and appealed to Chairman to say whether the Doctor-Baronet was in order. COURTNEY said, since he was asked, he must say he thought not. So FOSTER changed the prescription. CHAPLIN much gratified at this speedy close of rupture that threatened progress with Bill. Presided over discussion with urbanity that was irresistible.

"Reminds me," said WILFRID LAWSON, looking across at Right Hon. Gentleman seated on Treasury Bench, with deeply-bayed shirt-front, and head closely bent over copy of Bill, "of a motherly hen gathering its brood under its wings, and trying to make things comfortable all round. Sometimes, when one of the brood grows a trifle importunate, the motherly expression on the expansive face sharpens, and the chicken is pecked at. But, on the whole, little to disturb the serenity of the coop."

Never before thought of CHAPLIN as an old hen. But, really, with the place permeated with agricultural and farm-yard associations, LAWSON's idea not so far out of it as it might appear to the domestic circle at Blankney Hall.

At half-past eleven those Scotchmen came up again. Upset the henroost, devoured what was left of the cow, dug up the verdurous three acres, and till two o'clock in the morning harried the Commissioners under the Scotch University Act. Business done.—In Committee on the Small Holdings Bill.

Tuesday.—Don't know what we shall do when WIGGIN leaves us, as he threatens to do after Dissolution. Not much here just now, but sometimes his face seen in House or Lobbies, piercing surrounding gloom like what SWIFT MACNEILL distantly alludes to as "the orb of day." Only WIGGIN could have thought of the little divertissement that for a few moments raised depressed spirits of House this afternoon. Resumed at morning Sitting (so called because it takes place in the afternoon) discussion of Small Holdings Bill. SEALE-HAYNE,—whose reputation as a humorist still lingers a tradition in the playing fields at Eton, but whose subsequent political career has subdued his vivacity,—moved Amendment. Something about compensation for cow-sheds. COBB airily addressed the Committee; and CHAPLIN whispered a few confidential remarks across Table.

Curious how this "eminent authority," as the MARKISS calls quite another personage, has lost his voice since Bill got into Committee. Seems so awestruck by enormity of his responsibility, not inclined to raise his voice above whisper. Effort to catch purport of his remarks completed depression under which Committee sinking. Went out to vote as if they were conducting CHAPLIN to a too early funeral. Then it was that an idea dawned on the mind of the wanton WIGGIN.

"I'll show 'em sport, TOBY, dear boy," he said to me in passing. "I'll give their spirits a leg up!"

Forgotten about this in passing through Division Lobby; coming back startled by angry roar. COURTNEY on his feet solemnly shouting "Order, Order!" like minute-gun at sea. Nothing came of this; excitement increased; COURTNEY crying "Order, Order!" in sterner voice. Looked about for explanation, and lo! there was the waggish WIGGIN with his hat cocked well on one side of his head, waddling down the floor of the House past the Chair. You may do almost anything in the House of Commons but walk about with your hat on, and here was WIGGIN, not only doing it, but persisting in the offence, smiling back innocently on the increasing circle of Members roaring at him, and COURTNEY, with increasing stridency, shouting "Order!" behind his back. Having got nearly to the Bar, the wily WIGGIN, affecting to wonder what all the row was about, turned round and found himself pierced through and through with the flaming eye of outraged Chairman. Pretty to see how, all of a sudden, it seemed to flash upon him that he was the culprit, and that it was his hat at which Members, like so many WILLIAM TELLS, were persistently tiring. The sunset face flushed deeper still; with quick movement the wayward WIGGIN removed his offending hat, and, bowing apologetically to the Chair, went forth with quickened pace.

Excellently done; took in the whole House, including Chairman. But WIGGIN's benevolent intention secured, and, if only temporarily, spirits of House jubilantly rose. Business done.—In Committee on Small Holdings.

Wednesday.—Municipal Corporations Act, 1882 (Amendment) Bill first Order of Day. Doesn't seem to promise anything exciting; Debate, however, not gone far before discovery made that it hides a deep design. Wouldn't think, looking at FORWOOD as he sits at remote end of Treasury Bench, that he had anything to do with Hecuba, or Hecuba [pg 245] with him. Only suspicious thing about him is, his extreme desire to keep out of sight. When SPEAKER took Chair he was standing at Bar surveying House, and wondering when it would be made. As soon as MATTINSON rose to move Second Heading of Bill, FORWOOD. so to speak, went backward, and planted himself well in shadow of SPEAKER's Chair.

Turns out in course of interesting Debate that, though the speech on moving Second Reading is the voice of MATTINSON, the Bill is the Bill of FORWOOD, whose interest in the political affairs of Liverpool is said to be extensive and peculiar. NEVILLE puts it in another way. "Whenever," he said, "any political manipulation is afoot in Liverpool, be sure the Secretary to the Admiralty will not be far away."

At first, FORWOOD affected indifference to proceedings. "His Bill! s'elp him, never seen it before. 'L'pool.' What's that?" But as Debate went forward, and gentlemen opposite insisted on dragging him in, he finally yielded, and taking off coat, "went for" other side. Rev. SAM SMITH interposed with charming story about a gentleman whom Liverpool Tories had appointed Chairman of Watch Committee, "he being solicitor to the two largest publicans in Liverpool." That didn't at first sight seem much to point, supposing even the united cubit measurement of the worthy tradesmen exceeded twelve feet. But Reverend SAM went on to explain what he meant was that, "between them, they owned about 120 public-houses." Curious movement in Strangers' Gallery as of involuntary smacking of many lips, FORWOOD said this (which he daintily alluded to as "an allegation") had been denied. SAM, couching the retort in clerical language, said in effect, "You're another!" whereupon Ministerialists roared, "Oh! oh!" and FORWOOD, now thoroughly roused, proceeded to show that SAMUEL and his Liberal allies were the real Gerrymanders, and that he, FORWOOD, was the spotless advocate of the true interests of the Working-Man.

House began to look askance on S.S. Never suspected him of being a man of that kind. Glad when painful discussion came to end. Bill read Second Time; but jubilation of promoters suddenly chilled by TIM HEALY, of whom no one was thinking at the moment, stepping in and adroitly putting spoke in wheel of Bill, by moving to refer it to Select Committee; which, being translated, means it will get no Forwooder this Session.

Business done.—TIM HEALY puts FORWOOD's clock back.

Friday.—EDWARD WATKIN home from honeymooning trip. Pleased to find his Bill giving the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire Railway direct access to London passed all its stages in the Commons.

"It's a new way to London, good TOBY," he said, when I congratulated him on the double event. "Some gentlemen who faint in St. John's Wood objected on what I believe are called æsthetical grounds. But there are several big towns between here and Sheffield wanted the short cut, and I determined they should have it. Things looked bad last Session, and perhaps some fellows would have given up. I have a little way of never giving up, and it's astonishing how far it'll carry you. We're not through the Lords yet,—though, as you say, we are through their cricket-ground. But you'll see, before twelve months are over, I'll bring a train straight from Sheffield into our own station in London, and if you only live a little longer, you shall come with me on the first trip from Charing Cross to Paris under the Channel Tunnel. Everything, TOBY, cher ami, comes to the man who won't wait."

Business done.—Small Holdings Bill practically through Committee.

April 2, 1894.—The County Council at yesterday's meeting discussed the proposed new Tramway from Westminster Bridge to the Round Pond, through the Abbey, St. James's Park and Rotten Row. Deputations from all the artistic and archæological Societies presented petitions against it, but the Council refused to read them. Deputations from the Institute of Architects and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings also attended to give their views on the partial demolition of the Abbey, but they quarrelled so much amongst themselves that it was necessary to eject them, in order to prevent a free fight in the Council Chamber. Three Labour Candidates were then received, the Council standing respectfully, and stated that at least twenty-seven persons residing in Southwark would benefit by the direct route to Kensington Gardens. It was at once resolved that the Tramway should be made.

May 2, 1901.—Yesterday an immense Demonstration of Working-Men was held in Hyde Park to protest against the extension of the Tramways. Mr. JOHN SCALDS presided, and observed in his speech, "What is the good of taking the Working-Man from his own door to a park, if there is no park at the other end, only asphalte and tramlines and some stumps of trees cut down? What is the good of taking him to Westminster Abbey, if Poets' Corner has been made into a tramcar-shed? Besides, now the Working-Man is so much richer, and pays no rates or taxes, he does not want trams. They are only fit for the miserable Middle Class, and who cares about them?" This was greeted with loud shouts of, "Down with the Council!" and the vast assemblage marched with threatening cries and gestures towards the recently completed County Council Offices. Our readers are aware that this sumptuous building, which cost over two millions, occupies the site where St. Paul's Cathedral formerly stood. It was found, however, that the Council had suddenly adjourned, and that all the officials had fled. The workmen accordingly entered, and, having voted Mr. SCALDS to the chair, unanimously resolved that all the Tramways should be removed and the Parks replanted and returfed. It was decided that nothing could be done to replace the Cathedral or the Abbey, but it was resolved that the following inscription should be placed on the ruins at Westminster:—"To the lasting disgrace of the English Nation, this Building, together with the other beautiful and interesting parts of London, was ruined, for the sake of some impossible and imbecile schemes, by an assemblage of the most Despicable Dolts that ever lived."

The Minister. "WELL, JANET, HOW DID YOU LIKE YOUR NEW DOCTOR, DR. ELIZABETH SQUILLS?"

Janet. "WEEL, SIR, ONLY PRETTY WELL. YE SEE, SIR, DR. ELIZABETH ISN'T SO LEDDYLIKE AS SOME OF OUR AIN MEN DOCTORS!"

MIXED.—Under the heading "A Tragic Affair," it was recently stated in a paragraph, how "a Lady had been shot by a discharged Servant." It would have been better if the Servant, on being discharged, had gone off and injured nobody.

Effie (who can't make her sum come right). "OH, I DO WISH I WAS A RABBIT SO!"

Maud. "WHAT FOR, DARLING?"

Effie. "PAPA SAYS THEY MULTIPLY SO QUICKLY!"

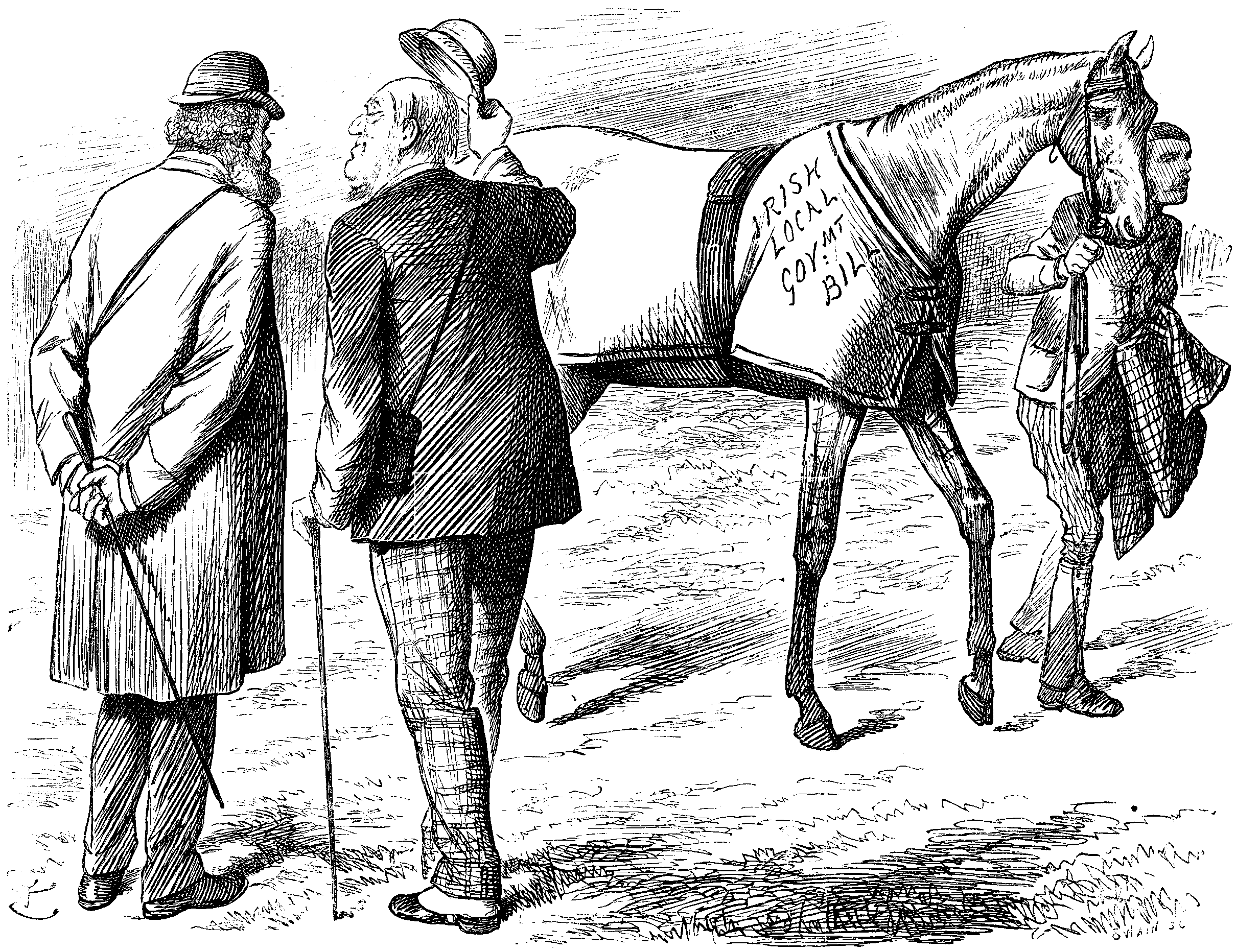

Noble Owner (watching the Favourite out for exercise).

Ah! don't look so bad, ARTHUR, after his spin!

They are asking all round if he'll run, if he'll win.

They would like much to know, I've no manner of doubt.

Why, there isn't a Bookie, a Tipster, or Tout,

Not to mention an Owner, or Trainer, or Vet,

But desires the straight tip—which I wish they may get!

If they knew he'd been "nobbled," they'd greatly rejoice;

Then they'd back other cracks—Dissolution for choice—

With a confident mind. "Nobbled!" Ah! were they able

To get at his groom, or sneak into his stable,

How gladly some of them would give him a dose!

That's right, ARTHUR; watch him, my lad, and—keep close!

Trainer. Ay, ay, Sir! They will not get much out of me, Sir!

A still tongue to Tipsters and Touts is a teaser.

They're awfully curious about t'other horse;

Dissolution, you know. Try to pump me.

Noble Owner. Of course!

Very natural, you know, I should be, in their case.

If they knew that this nag couldn't win the big race,

Or was not meant to run, then their course would be clear.

[Espies Stranger approaching.

Hillo! Not too near, ARTHUR! (Aside.) Whom have we here?

Polite Stranger (insinuatingly).

Beg pardon, my Lord! A bit out of my track.

Missed my way. But—ahem!—is that really the "crack"?

Why, he looks cherry ripe—at a distance. I've heard

All sorts of reports—gossips are so absurd!

But—would you mind telling me—has the Great Horse

Been really—got at? Entre nous, mind!—

Noble Owner (drily). Of course!

Dissolution's shy backers would much like to know.

But—tell them who sent you to ask—it's no go!

[Exit, leaving Polite Stranger planté là.

Thou shalt not steal! That's a command

Which grips us with an iron hand;

And "he who prigs what isn't his'n,

When he is cotched shall go to prison!"

So runs the Cockney doggerel, clear

If ungrammatical, austere,

With not a saving clause to qualify

Its rigid Spartan rule, or mollify

Theft's Nemesis. Thou shalt not steal!

At least,—ahem!—well, all must feel

That property in thoughts and phrases,

The verbal filagree that raises

Flat fustian into "oratory,"

And makes the pulpit place of glory,

Such property is not so easy

To settle, and a conscience queasy

O'er picking pockets, oft remains

Quite unperturbed while—picking brains!

A Sermon is not minted coin;

It you may borrow, buy, purloin,

In part or wholly, and yet preach it

As your own work. Who'll dare impeach it,

This innocent transaction? Not

Your "brethren," save, perchance, some hot

And ultra-honest (which means "rancorous")

Parsonic rival. "How cantankerous!"

The reverend Assembly shouts.

It mocks at scruples, flames at doubts,

Hints at the stern objector's animus,

In the prig's praises is unanimous.

Oh, Happy Cleric Land, where unity

Breeds such unquestioning community

Of property—in Sermons! True it

Strikes some as queer; but they all do it,

If one may trust advertisement,

And an Assembly's calm content

At what to the Lay mind seems robbery.

Steal? Nay! But do not raise a bobbery,

If hard-up preachers glean their shelves

And take the credit to themselves.

How wise, how good, how kind, how just!

And how the poor Lay mind must trust

Those who so skilfully reveal

The meaning of "Thou shalt not Steal!"

"REGRETS AND GREAVES."—But for a recent trial, who of the outside public would even have guessed that the unromantic and quite Bozzian name of "Mr. and Mrs. TILKINS" meant the clever musician, Mr. IVAN CARTEL and the charming and accomplished actress and soprano, Miss GERALDINE ULMAR? The TILKINSES are to be congratulated on their winning the recent action of Tilkins v. Greaves with the award of one thousand pounds damage, which is the price the transmitter of scandal to the New York World has had to pay for his industry.

POLITE STRANGER. "I BEG YOUR PARDON, SIR: WOULD YOU KINDLY INFORM ME IF HE'S BEEN—'GOT AT'?"

NOBLE OWNER. "H'M!—AH!—WOULDN'T THE BACKERS OF DISSOLUTION LIKE TO KNOW!"

Most Cookery-Books are bosh. I have read them all—from the 'Αρχιμαγειρος of FRANCATELLIDES (1904 B.C.) to the Ayer Akberi: or Million Recipes of RUNG JUNG JELLYBAG, compiled in Sanskrit, Pali, Singhali, Urdu, Hindustani, Bengali, and the Marowsky language, for the "Kitchens measureless to man" (see COALRIDGE), of the Golden Dome of Kubla Khan; from Mrs. GLASSE to Dr. KITCHENER; from UDE to ALEXANDRE DUMAS; from CARÊME to Mrs. MARKHAM (who is said to have adopted the pseudonym of "RUNDELL" for her culinary mistress-piece); and from Miss ACTON (who was also the distinguished authoress of Austen Fryers, Pies and Prejudice, Sense and Saltcellars, &c.) to SOYER. The only modern culinary manual which (with one exception) is worth anything is by Mrs. DE SALIS, whose name has a happy affinity to that of The Only Trustworthy Authority as a Cookery-Bookerist, and whose immortal contributions to mageiristic lore are appearing weekly in Sal—— (Here the M.S. is firmly scored out by the Editorial blue pencil; but, faintly legible, is, "circulation, 2,599,862-3/8.") From this "Golden Treasury" of gormandising I have been permitted to cull a few recipes. Here are two or three for scholastic bed-room suppers. The first will be invaluable in Seminaries for Young Ladies:—

Saucissons en Petite Toilette.—Purchase your sausages on the sly, and keep them carefully in your glove-box, or your handkerchief case till wanted. Prick them all over with a hair-pin before cooking. Sprinkle them lightly with violet powder, and fry in cold cream (bear's grease will do as well) on the back of your handglass over the bed-room candle. If the glass gets broken, say it was the housemaid, or the cat did it. Turn with the curling-tongs. When done to a rich golden brown, put your sausages on a neatly folded copy of S—— (Editorial blue pencil again), and serve hot. Thin bread and butter, plum-cake or shortbread may accompany this appetising dish, and a partially ripe apple munched between each sausage will certainly give it a zest; but it would perhaps be as well not to eat too many chocolate creams afterwards.

Soufflé de Fromage de Hollande.—This is a very favourite dish for the dormitory in Young Gentlemen's schools. Procure, on credit, a fine Dutch cheese, keep it carefully in your play-box or in your desk; but don't let your white mice get at it. Before cooking in the dormitory, you and your young friends can have a nice game of ball with the merry Dutchman, only refrain from trying his relative hardness or softness by hammering the head of MUGG, the stupidest boy in the school, with it. Now cut up your cheese into small dice and carefully toast them on a triangular piece of slate, which you will cause "GYP Minor" to hold over a spirit-lamp. When, as the slate grows hotter, "GYP Minor" will probably howl, box his ears smartly, and the cheese will thus become a "soufflé," or rather "soufflet." Serve à la main chaude, but I must indignantly protest against the practice of some youths of eating peppermint drops with this "plat." A bath bun is much better. Beverage, gingerbeer or a little ginger wine.

Tournedos à la Busby.—It is a very astonishing thing that I never could persuade school-boys that this is a most succulent, scholastic supper-dish, exceptionally brisk and pungent in its flavour. Perhaps their aversion to it is based on the fact that the tournedos is usually served very hot indeed towards the conclusion of the repast by the Rev. Principal. It is accompanied by a brown sauce made of a bouquet de bouleau full of buds and marinaded in mild pickle.

Curried Rabbit.—Proceed to Ostend and procure a rabbit; honestly if possible, but procure it. Pinch its scut or bite its ears, and when it exclaims, "Miauw!" it is not a genuine rabbit, but a grimalkin in disguise. Some cats are very deceitful at heart. Bring your rabbit home, and then send to the nearest livery stables and borrow a curry-comb, then proceed to curry your rabbit. If Bunny resists, hit him over the head with the comb. He will possibly run away to rejoin his brethren at Ostend, or in New South Wales; but at all events you will have the curry-comb. One can be good and happy without returning the things you borrow. See my "Essay on Books, Cartes-de-visite, and Umbrellas," in the next number of Sala's J—— (Editorial blue-pencil again.)

Potage à la Jambe de Bois (Wooden-leg Soup).—Procure a fine fresh wooden-leg, one from Chelsea is the best. Wash it carefully in six waters, blanch it, and trim neatly. Lay it at the bottom of a large pot, into which place eight pounds of the undercut of prime beef, half a Bayonne ham, two young chickens, and a sweetbread. To these add leeks, chervil, carrots, turnips, fifty heads of asparagus, a few truffles, a large cow-cabbage, a pint of French beans, a peck of very young peas, a tomato cut in slices, some potatoes, and a couple of bananas. Pour in three gallons of water, and boil furiously till your soup is reduced to about a pint and a-half. As it boils, add, drop by drop, a bottle of JULES MUMM's Extra Dry, and a gill of Scotch whiskey; then take out your wooden leg, which wipe carefully and serve separately with a neat frill, which can be easily cut from the cover of Sala's Jo—— (Editorial blue pencil again), round the top. The soup itself is best served in a silver tureen, or in a Dresden china punch-bowl. The above obviously is intended neither for school-boys nor school-girls, nor is it meant for the tables of the wealthy and luxurious. It is emphatically a Poor Man's Dish, otherwise it would never have found a place in the cookery column of that essentially popular periodical, Sala's Journal. Hurrah! the Editor has gone out to "chop," and there was no blue pencil to mar the last touching allusions. N.B.—Circulation, eight millions, nine hundred and thirty-three thousand, two hundred and sixty-one and a-half. Guaranteed by five firms of Magna Chartered Accountants.

Mr. STUART RENDEL, having stated at Llanfair-Caerecinion that "a day with Mr. GLADSTONE was a whole liberal education," the London School Board has at last decided to alter the present system completely. After many days' deliberation, it has been arranged to hire the Albert Palace and Mr. GLADSTONE for a week. It is estimated that during six days, all the children now in the London schools can, in detachments, be squeezed into the building and spend a day there with the Right Honourable Gentleman. Seats will be provided on the platform for the Members of the Board, as this instruction would be a great benefit to many of them. At the end of the six days the present work of the Board will be finished, and it will adjourn for ten years, when another week in the society of the Grand Old Educator will again suffice for the needs of the rising generation. The numerous Board Schools will therefore become useless, but it is not proposed to demolish them, as experience has shown that they are sure to fall down of their own accord before long. The sumptuous offices of the Board will be converted into a Home for Destitute Schoolmasters.

We have reason to believe that Mr. GLADSTONE, after fulfilling his engagement at the Albert Palace, will make a tour in the provinces, and later on will have classes for journalists and other literary men, whose style, in many cases, would be vastly improved by two minutes, or even less, in the same room with him.

"A jolly place," said he, "in times of old.

But something ails it now: the place is curst."

A residence for Tory, Whig or Rad,

Where yet none had abiding habitation;

A House—but darkened by the influence sad

Of slow disintegration.

O'er all there hung a shadow and a fear,

A sense of mystery the spirit daunted,

And said as plain as whisper in the ear,

The place is Haunted!

There speech grew wild and rankly as the weed,

GRAHAM with TANNER waged competitive trials,

And vulgar bores of Billingsgatish breed

Voided spleen's venomed vials.

But gay or gloomy, fluent or infirm,

None heeded their dull drawls, of hours' duration.

The House was clearly in for a long term

Of desolate stagnation.

The SPEAKER yawned upon his Chair, he found

It tiring work, a placid brow to furrow,

To sit out speeches arguing round and round,

From County or from Borough.

The Members, like wild rabbits, scudded through

The lobbies, took their seats, lounged, yawned—and vanished.

The Whips like spectres wandered; well they knew

All discipline was banished.

The blatant bore,—the faddist, and the fool,

Were listened to with an indifferent tameness.

The windbag of the new Hibernian school

Railed on with shocking sameness.

The moping M.P. motionless and stiff,

Who, on his bench sat silently and stilly,

Gawped with round eyes and pendulous lips, as if

He had been stricken silly:

No cheery sound, except when far away

Came echoes of 'cute LABBY's cynic laughter,

Which, sick of Dumbleborough's chattering jay,

His listeners rambled after.

But Echo's self tires of a GRAHAM's tongue,

Rot blent with rudeness gentlest nymph can't pardon.

Why e'en the G.O.M. his grey head hung,

And wished he were at Hawarden.

Like vine unpruned, SEXTON's exuberant speech

Sprawled o'er the question with the which he'd grapple;

PICTON prosed on,—the style in which men preach

In a dissenting chapel.

Prince ARTHUR twined one lank leg t'other round,

Drooping a long chin like BURNE-JONES's ladies;

And HARCOURT, sickening of the strident sound,

Wished CONYBEARE in Hades.

For over all there hung a cloud of fear,

A sense of imminent doom the spirit daunted,

And said, as plain as whisper in the ear,

The House is Haunted!

Oh, very gloomy is this House of Woe,

Where yawns are numerous while Big Ben is knelling.

It is not on the Session dull and slow,

These pale M.P.'s are dwelling.

Oh, very, very dreary is the gloom,

But M.P.'s heed not HEALY's elocution;

Each one is wondering what may be his doom

After the Dissolution!

That House of Woe must soon be closed to all

Who linger now therein with tedium mortal,

And of those lingerers a proportion small

Again may pass its portal.

There's many a one who o'er its threshold stole

In Eighty-Six's curious Party tangle,

Who for the votes which helped him head the poll

In vain again may angle.

The GRAHAMS and the CALDWELLS may look bold,

So may the CONYBEARES, and COBBS and TANNERS;

But the next House quite other men may hold,

And (let's hope) other manners.

They'd like to know when this will close its door

Upon each moribund and mournful Member,

And who will stand upon the House's floor

After, say, next November.

That's why the M.P.'s sit in silent doubt,

Why spirits flag, and cheeks are pale and livid,

And why the DISSOLUTION SPOOK stands out

So ominously vivid.

Some key to the result of the appeal

They yearn for vainly, all their nerves a-quiver;

The presence of the Shadow they all feel,

And sit, and brood, and shiver.

There is a sombre rumour in the air,

The shadow of a Presence dim, atrocious;

No human creature can be festive there,

Even the most ferocious.

An Omen in the place there seems to be,

Both sides with spectral perturbation covering.

The straining eyeballs are prepared to see

The Apparition hovering.

With doubt, with fear, their features are o'ercast;

SALISBURY at Covent Garden might have spoken,

But, save for Rumour's whispers on the blast,

The silence is unbroken.

And over all there hangs a cloud of fear,

The Spook of Dissolution all has daunted,

And says as plain as whisper in the ear,

The House is Haunted!

Husband. "OH, SIR JOHN, SO GLAD YOU HAVE CALLED!—AND SO KIND OF LADY DASHWOOD TO HAVE ASKED us TO HER PARTY!—BUT WE ARE QUITE IN A FIX WHEN TO COME, BECAUSE THE CARD SAYS 'EARLY AND LATE.'"

Sir John. "OH, I THINK I CAN TELL YOU. SEND YOUR WIFE VERY EARLY INDEED, AND YOU CAN COME AS LATE AS YOU LIKE!"

Husband (who does not quite see it). "THANKS! THANKS! VERY MANY THANKS!"

"Upon what principle," one of my Baronites writes, "do people collecting a number of short stories for publication in one volume, select that which shall give the book its title?" Of course I know, but shan't say; am not here to answer conundrums. After interval of chilling silence, my Baronite continues, "Lady LINDSAY has brought together ten stories which A. & C. BLACK publish in a comely volume. She calls it A Philosopher's Window, that being the title of the first in the procession. I have looked through the Philosopher's Window, and don't see much, except perhaps a reminiscence of A Christmas Carol. There are others, far better, notably 'Miss Dairsie's Diary.' This is a gem of simple narrative, set in charming Scottish scenery, which Lady LINDSAY evidently knows and loves. There is much else that is good. 'The Story of a Railway Journey,' and 'Poor Miss Brackenthorpe,' for example. All are set in a minor key, but it is simple, natural music."

Any woman, my dear young girls, can marry any man she likes, provided that she is careful about two points. She must let him know that she would accept a proposal from him, but she must never let him know that she has let him know. The encouragement must be very strong but very delicate. To let him know that you would marry him is to appeal to his vanity, and this appeal never fails; but to let him know that you have given him the information is to appeal to his pity, and this appeal never succeeds. Besides, you awake his disgust. Half the art of the woman of the world consists in doing disgusting things delicately. Be delicate, be indirect, avoid simplicity, and there is hardly any limit to your choice of a husband.

I need say nothing about detrimental people. The conflict between a daughter and her parents on this point—so popular in fiction—very rarely takes place. It is well understood. You may fall in love with the detrimental person, and you may let him fall in love with you. But at present we are talking about marriage. Never marry a man with the artistic temperament. By the artistic temperament one means morbid tastes, uncertain temper and excessive vanity. It may be witty at dinner; it must be snappish at breakfast. It never has any money. In its dress it is dirty and picturesque, unless under the pressure of an occasion. It flirts well, but marries badly. I have described, of course, rather a pronounced case of artistic temperament. But it is hardly safe to marry any man who appreciates things artistic, because, as a rule, he only does it in order that people may appreciate his appreciation; and after a time that becomes wearisome.

Do not marry an imperial man. The young girl of seventeen believes in strength; by this she means a large chin and a persistent neglect of herself. She adores that kind of thing, and she will marry it if she is not warned. It is not good to fall in love with Restrained Force, and afterwards find that you have married Apathy.

The man whom you marry must, of course, have an income; he should have a better social position than you have any right to expect. You know all that—it is a commonplace. But also he must be perfectly even. In everything he should remind you constantly of most other men. Everything in him and about him should be uniform. Even his sins should be so monotonous that it is impossible to call them romantic. Avoid the romantic. Shun supreme moments. Chocolate-creams are very well, but as a daily food dry toast is better. Seek for the man who has the qualities of dry toast—a hard exterior manner, and an interior temperament that is at once soft and insipid. The man that I describe is amenable to flattery, even as dry toast is amenable to butter. You can guide him. And, as he never varies, you can calculate upon him. Marry the dry-toast man. He is easy to obtain. There are hundreds of him in Piccadilly. None of them wants to marry, and all of them will. He gives no trouble. He will go to the Club when he wants to talk, and to the theatre when he wants to be amused. He will come to you when he wants absolutely nothing; and in you—if you are the well-bred English girl that I am supposing—he will assuredly find it. And so you will both be contented.

Do not think that I am, for one moment, depreciating sentiment. I worship it; I am a sentimentalist myself. But everything has its place, and sentiment of this kind belongs to young unmarried life—to the period when you are engaged, or when you ought to be engaged. The young man whom I have described—the crisp, perfect, insipid, dry-toast man—would only be bored by a wife who wanted to be on sentimental terms with him. I remember a case in point. A young girl, whom I knew intimately, married a man who was, as a husband, perfect. They lived happily enough for three or four years; she had a couple of children, a beautiful house, everything that could be desired. And then the trouble came. She had been reading trashy novels, I suppose; at any rate, she fell in love with her own husband. She went in daily dread that he would find it out. I argued with her, reasoned with her, entreated her to give up such ruinous folly. It was of no use. She wrote him letters—three sheets, crossed and underlined. I warned her that sooner or later he would read one of them. He did; and he never forgave her. That happy home is all broken up now—simply because that woman could not remember that there is a time for sentiment and a time for propriety, and that marriage is the time for propriety. The passions are all very well until you are married; but the fashions will last you all your life.

I have no more to say on the choice of a husband. It is quite the simplest thing that a young girl has to learn,—you must find a quite colourless person, and flatter him a little; his vanity will do the rest. And when you are married to him, you will find him much easier to tolerate than a man who has any strong characteristic. Do not get into the habit of thinking marriage important; it is only important in so far as it affects externals; it need not touch the interior of your life.

I have received several letters. ELLA has had poetry sent to her by her fiancé, and wishes to know if this would justify her in breaking the engagement. I think not. She can never be quite certain that it is the man's own make; and, besides, plenty of men are like that during the engagement period, but never suffer from it afterwards. The other letters must be answered privately.

Have you heard the Yankee threat to suppress the Cigarette?

Ten dollars tax per thousand—as the French would say, par mille—

Is the scheme proposed, forsooth, to protect the Yankee youth

From poisons just discovered in his papier pur fil!

Such things might well have been in staring emerald green,

Or even in the paler tint that's christened "Eau-de-Nil,"

But it simply makes one sick to imagine arsenic

Is lurking in the spotless white of papier pur fil!

Strange the smoking French survive! Surely none should be alive;

Fair France should be one mighty morgue from Biarritz to Lille,

If there's also phosphorus, bringing deadly loss for us,

In Hygiene's new victim, luckless papier pur fil.

Yet some Frenchmen live to tell they are feeling pretty well;

From dozing Concierge at home to marching Garde Mobile,

You might safely bet your boots that, with loud derisive hoots,

They'd scout the thought of poison in their papier pur fil.

Then how foolish to conclude that, because they hurt the dude,

Smoking all day in the country, half the night as well en ville,

After dinner Cigarettes, two or three, mean paying debts

Of nature, or mean going mad, from papier pur fil!

SIR,—I am going to start a Caravan! It's all the go now, and nothing like it for fresh air and seeing out-of-the-way country places. What's the good of Hamlet with all the hamlets left out, eh? We shall sleep in bunks, and have six horses to pull us up any Bunker's Hill we may come to. I intend doing the thing in style, like the Duke of NEWCASTLE and Dr. GORDON STABLES, No gipsying for yours truly! I've been calculating how many people I shall want, and I don't think I can get on comfortably without all the following (they'll be my following, d'ye see?):—

1. Head Driver; 2. Understudy for Driver; 3. Butler; 4. Footman; 5. Veterinary Surgeon; 6. Carpenter (if wheel comes off, &c.); 7. Handy working Orator (to explain to people that we're not a Political Van); 8. Electrician (in case horses go lame, and we have to use electricity); 9, 10, 11. Female Servants.

The Servants will have to occupy a separate van, of course. They'll be in the van and in the rear at the same time! I'll let your readers know how we get on. At present we haven't even got off.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

***END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI, VOL. 102, MAY 21, 1892***

******* This file should be named 14695-h.txt or 14695-h.zip *******

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/4/6/9/14695

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS,' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/pglaf.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://www.gutenberg.org/about/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/pglaf

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit:

https://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Each eBook is in a subdirectory of the same number as the eBook's

eBook number, often in several formats including plain vanilla ASCII,

compressed (zipped), HTML and others.

Corrected EDITIONS of our eBooks replace the old file and take over

the old filename and etext number. The replaced older file is renamed.

VERSIONS based on separate sources are treated as new eBooks receiving

new filenames and etext numbers.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.

EBooks posted prior to November 2003, with eBook numbers BELOW #10000,

are filed in directories based on their release date. If you want to

download any of these eBooks directly, rather than using the regular

search system you may utilize the following addresses and just

download by the etext year.

https://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext06/

(Or /etext 05, 04, 03, 02, 01, 00, 99,

98, 97, 96, 95, 94, 93, 92, 92, 91 or 90)

EBooks posted since November 2003, with etext numbers OVER #10000, are

filed in a different way. The year of a release date is no longer part

of the directory path. The path is based on the etext number (which is

identical to the filename). The path to the file is made up of single

digits corresponding to all but the last digit in the filename. For

example an eBook of filename 10234 would be found at:

https://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/0/2/3/10234

or filename 24689 would be found at:

https://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/2/4/6/8/24689

An alternative method of locating eBooks:

https://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/GUTINDEX.ALL

*** END: FULL LICENSE ***