Transcriber’s Note: Obvious errors in spelling and punctuation have been corrected. Footnotes have been moved to the end of the text body. Also images have been moved from the middle of a paragraph to the closest paragraph break, causing missing page numbers for those image pages and blank pages in this ebook.

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

CLEVELAND, OHIO

1902

COPYRIGHT, 1902

BY

The Arthur H. Clark Company

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

TO

MY FATHER

THIS SERIES OF VOLUMES

IS AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED

“Je n’aurais point aux Dieux demandé d’autre père.”

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | 11 | |

| General Introduction | 17 | |

| PART I | ||

| I. | The Comparative Method of Study | 37 |

| II. | Distribution of Mound-building Indians | 43 |

| III. | Early Travel in the Interior | 53 |

| IV. | Highland Location of Archæological Remains | 68 |

| V. | Watershed Migrations | 94 |

| PART II | ||

| I. | Introductory | 101 |

| II. | Range and Habits of the Buffalo | 103 |

| III. | Early Use of Buffalo Roads | 110 |

| IV. | Continental Thoroughfares | 128 |

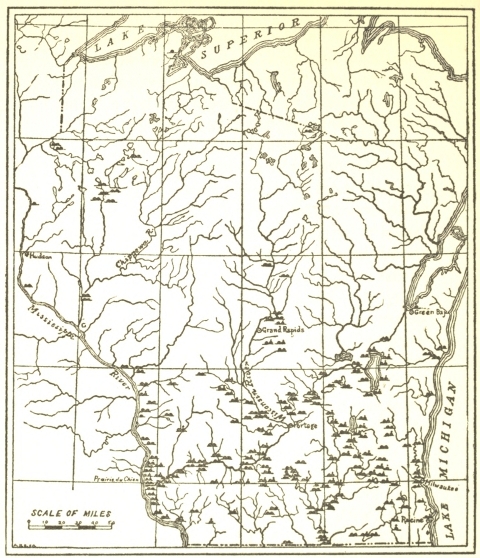

| I. | Archæologic Map of Wisconsin (showing interior location of remains) | 48 |

| II. | Archæologic Map of Ohio (showing interior location of remains) | 52 |

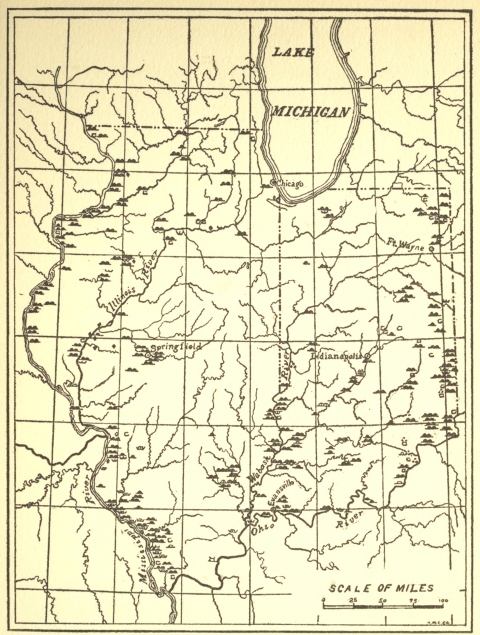

| III. | Archæologic Map of Illinois and Indiana (showing interior location of remains) | 55 |

| IV. | Early Highways on the Watersheds of Ohio | 78 |

Beginning with the first highways of America, the first monograph of the series will consider the routes of the mound-building Indians and the trails of the large game animals, particularly the buffalo, as having set the course of landward travel in America on the watersheds of the interior of the continent. The second monograph will treat of the Indian thoroughfares of America; the third, fourth, and fifth, the three roads built westward during the old French War, Washington’s Road (Nemacolin’s Path), Braddock’s Road, and the Old Glade (Forbes’s) Road. The sixth monograph will be a study of Boone’s Wilderness Road to Kentucky; the seventh and eighth, a study of the principal portage paths of the interior of the continent and of the military roads built in the Mississippi basin during the era of conquest;[Pg 12] Vol. IX. will take up the historic water-ways which most influenced westward conquest and immigration; the famed Cumberland Road, or Old National Road, “which more than any other material structure in the land served to harmonize and strengthen, if not to save, the Union,” will be the subject of the tenth monograph. Two volumes will be given to the study of the pioneer roads of America, and two to the consideration of the history of the great American canals.

The history of America in the later part of the pioneer period, between 1810 and 1840, centers about the roads and canals which were to that day what our trunk railway lines are to us today. The “life of the road” was the life of the nation, and a study of the traffic on those first highways of land and water, and of the customs and experiences of the early travelers over them brings back with freshening interest the story of our own “Middle Age.” Horace Bushnell well said: “If you wish to know whether society is stagnant, learning scholastic, religion a dead formality, you may learn something by going[Pg 13] into universities and libraries; something also by the work that is doing on cathedrals and churches, or in them; but quite as much by looking at the roads. For if there is any motion in society, the Road, which is the symbol of motion, will indicate the fact. When there is activity, or enlargement, or a liberalizing spirit of any kind, then there is intercourse and travel, and these require roads. So if there is any kind of advancement going on, if new ideas are abroad and new hopes rising, then you will see it by the roads that are building. Nothing makes an inroad without making a road. All creative action, whether in government, industry, thought, or religion, creates roads.” The days when our first roads and our great canals were building, were days when “new ideas were abroad and new hopes rising.” The four volumes of our series treating of pioneer roads and the great canals will be a record of those ideas and hopes and the mighty part they played in the social development of America. The final volume will treat of the practical side of the road question. An index will conclude the series.

Nothing is more typical of a civilization than its roads. The traveler enters the city of Nazareth on a Roman road which has been used, perhaps, since the Christian era dawned. Every line is typical of Rome; every block of stone speaks of Roman power and Roman will. And ancient roads come down from the Roman standard in a descending scale even as the civilizations which built them. The main thoroughfare from the shore of the Yellow Sea to the capital of Korea, used by millions for millenniums, has never been more than the bridle path it is today—fit emblem of a people without a hope in the world, an apathetic, hermit nation.

Every road has a story and the burden of every story is a need. The greater the need, the better the road and the longer and more important the story. Go back[Pg 18] even to primeval America. The bear’s food was all about him, in forest and bush. He made no roads for he needed none, save a path into the valley. But the moose and deer and buffalo required new feeding-grounds, fresh salt licks and change of climate, and the great roads they broke open across the watersheds declare nothing if not a need.

The ancient Indian confederacies which tilled the soil of this continent and built great mounds for defense and worship—so great, indeed, that the people have even been known as “mound-builders”—undoubtedly first traveled the highest highways of America. Some of them may have known the water-ways better than any of the land-ways—for their signal stations were erected on the shores of many of our important rivers—but the location of their heaviest seats of population was where we find the richest lands and the heaviest populations today, and that is in what may be called the interior of the continent, or along the smaller rivers. Such stupendous works as Fort Ancient and Fort Hill are located beside very inferior streams, and[Pg 19] between such works as these, placed without any seeming regard for the larger water-ways, these mound-building Indians must have had great thoroughfares along the summits of the watersheds. About these earthworks they constructed great, graded roadways, commensurate with the size of the works of which they were a necessary part, but so far as we know these early peoples built no roads between their forts or between their villages. They made no thoroughfares.

It was for the great game animals to mark out what became known as the first thoroughfares of America. The plunging buffalo, keen of instinct, and nothing if not a utilitarian, broke great roads across the continent on the summits of the watersheds, beside which the first Indian trails were but traces through the forests. Heavy, fleet of foot, capable of covering scores of miles a day, the buffalo tore his roads from one feeding-ground to another, and from north to south, on the high grounds; here his roads were swept clear of débris in summer, and of snow in winter. They mounted the heights and descended from[Pg 20] them on the longest slopes, and crossed each stream on the bars at the mouths of its lesser tributaries.

Evidence remains today to show what great thoroughfares these buffalo roads were, for on the summit of many of the greater watersheds may be seen the remains of the old courses, and there the hoofprints of centuries of travel may yet be read. If the summit should be bare of trees, the very contour of the ground may suggest the old-time, deeply-trod roadway; where a forest lies over the summit a remarkably significant open aisle in the woods speaks yet more plainly of the ancient highway, where only shrubs and little trees are found in the center of the track.

It is very wonderful that the buffalo’s instinct should have found the very best courses across a continent upon whose thousand rivers such great black forests were thickly strung. Yet it did, as the tripod of the white man has proved; and until the problem of aërial navigation is solved, human intercourse will move largely on paths first marked by the buffalo. It is[Pg 21] interesting that he found the strategic passage-ways through the mountains, so that the first explorers came into the West through gaps where were found broad buffalo roads; it is also interesting that the buffalo marked out the most practical portage paths between the heads of our rivers—paths that are closely followed today, for instance, by the Pennsylvania and Baltimore and Ohio railways through the Alleghanies, the Chesapeake and Ohio through the Blue Ridge, the Cleveland Terminal and Valley railway between the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas rivers and the Wabash railway between the Maumee and Wabash rivers. In one instance (that of the Cuyahoga-Tuscarawas portage) the route of the ancient portage—most plainly to be discovered because it was for so long a time the boundary of the United States that lands on the west of it were surveyed by a different system from those on the east—is crossed by a modern road seven times in a distance of eight miles.

But the greater marvel is that these early pathfinders chose routes, even in the roughest districts, which the tripod of the white[Pg 22] man cannot improve upon. A rare instance of this is the course of the Baltimore and Ohio railway between Grafton and Parkersburg in West Virginia. That this is one of the roughest rides our palatial trains of today make is well known to all who have passed that way, and that so fine a road could be put through such a rough country is one of the marvels of engineering science. But leave the train, say, at the little hamlet of Petroleum, West Virginia, and find on the hill the famous old-time thoroughfare of the buffalo, Indian, and pioneer and follow that narrow “thread of soil” westward to the Ohio river. You will find that the railway has followed it steadily throughout its course and when it came to a more difficult point than usual, where the railway is compelled to tunnel at the strategic point of least elevation, in two instances the trail runs exactly over the tunnel. This occurs at both “Eaton’s” tunnel, and “Gorham’s” tunnel (or “No. 6”).

With the deterioration of the civilization to which the mound-building Indians belonged, the art of road-building became lost—for the great need had passed away.[Pg 23] The later Indians built no such roads as did their ancestors, nor did they improve such routes on the highways as they found or made. But they collected poll-taxes from travelers along them, setting an example to generations of county commissioners who collect taxes for roads they do not improve.

That the later Indians used the paths made by the buffalo they hunted is beyond question. Warring Indian nations lured each other into ambush by stamping a buffalo hoof upon the soft ground in their trail. And when, later, Daniel Boone hewed his path through Cumberland Gap toward Kentucky, he plainly says that he left the Indian road on Rockcastle river and marked out the remainder of his way over a buffalo trace.

The great Indian trails, covering the land as with a network, and leading by the straightest practicable courses to all strategic points, became of momentous importance to the white man when he turned his attention to the interior of the continent. When the Indian learned the value of his furs, a great tide of trade set eastward over a thousand rivers and woodland trails. On[Pg 24] these same rivers, but more frequently on the trails, white traders ventured westward with their bright wares—and the western land became known among a much larger coterie than before. The tales of the traders, together with dreams of commercial exploitation led to the first careful exploration of the interior of the continent by such men as Walker, Gist, Boone, and Carver, to whom these narrow “roads of iron,” as the Jesuit missionaries in the north called the rough Indian trails, were shining paths to an El Dorado. The first two great roads built westward were opened under the direction of trading companies: the road from the Potomac to the Ohio by Captain Cresap, for the first Ohio Company, and the road from Virginia to Kentucky by Daniel Boone, for the Transylvania Company. And these were at first only blazed and widened Indian thoroughfares which had been used from times prehistoric.

The missionaries, too, were great explorers, and they knew the Indian thoroughfares perhaps better even than the traders; at least they knew some that white men had never traveled before them.[Pg 25]

“Whither is the paleface going?” asked an old Seneca chieftain of the indomitable Zeisberger; “why does the paleface travel such unknown roads? This is no road for white people and no white man has come this trail before.”

“We reached home very late at night,” wrote a brave Jesuit, “after considerable trouble—for the paths were only about half a foot wide where the snow would sustain one, and if you turned ever so little to the right or left you were in it half way up to your thighs.”

When the land was once discovered, its conquest was directed along the very paths on which these explorers came. To the armies which conquered the West the Indian thoroughfares were indispensable. Washington followed narrow Indian trails while on his mission to the French on the Allegheny in 1753; in the year following he widened Nemacolin’s Path across the mountains over which he hauled his swivels to Fort Necessity. Braddock followed the same rough path in the succeeding year, making a great gorge of a road which, after a century and a half, we can[Pg 26] follow as plainly as a new-made furrow behind a plow—even to the ford and charnel-ground where the thin red line was swept away in that torrent of lurking flame. Three years later, prejudiced against Virginia’s Braddock Road, the dying but indomitable Forbes—truly, as the Indians called him, a Head of Iron—mowed another swath of a road westward through Carlisle and Bedford to Fort Duquesne, that Pennsylvania herself might have a road through her own province to the Ohio river. Braddock’s Road paused abruptly on the brink of a bloody ravine seven miles from Pittsburg; but the home-stretch of the road built by this Head of Iron is the beautiful Forbes Avenue of today.

The Great Trail of the West was the highway between Pittsburg and Detroit, and its story is the bloody story of the Revolutionary War in the West. For centuries this path had been a famed thoroughfare, throwing its great sinuous lengths over the watersheds from the lakes to the “Forks of the Ohio.” Over this track the brave Swiss Bouquet led the first English army that crossed the Ohio river, making a[Pg 27] tri-track road to the Muskingum valley and bringing to a triumphal close Pontiac’s bloody rebellion. The old Iroquois trail up the Mohawk valley and across the great watershed of New York to the Niagara river was a famous Revolutionary highway and afterward became one of the important pioneer routes. On the Great Trail to Detroit Lachlan McIntosh erected the first fort built by the thirteen colonies west of the Ohio, Fort Laurens on the Muskingum near Great Crossings, where Bouquet had thrown his army across the river in 1764. Indeed, throughout that whole half-century of conflict in the Central West the lines of conquest were the lines of the earlier routes of travel. Washington, Braddock, Forbes, Bouquet, Lewis, Shirley, Sullivan, Clark, Brodhead, Crawford, Irvine, McIntosh, Harmar, St. Clair, Wayne, and Harrison followed these old highways and fought their battles on and beside them. These campaigns were not made by water but by land. Had they been made by rivers, the courses of their routes would have been frequently described and mapped as having an important[Pg 28] bearing on the history of each campaign. Because they were made by land over routes which have never received attention from historians the real ground-work of these campaigns has been entirely omitted. Each would be far better understood in every way if its route were clearly defined. A thorough understanding of our history is impossible without a knowledge of these highways of trade and war and the strategic points they covered and connected.

But of vaster interest is the study of the surging armies of pioneers and the occupation of the great empire conquered by these armies for them. To the emigrant each tawny trail was a path to a Promised Land. They came in thousands and hundreds of thousands over the roads of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. And what roads they were! It was impossible for those pioneer wagons to follow the Indian paths with any exactness. Even Braddock avoided the steeper hills and yet was compelled to lower his wagons from some hills with blocks and tackling—many being demolished at that. And yet to[Pg 29] avoid the high ground was inevitably to run into bogs and swamps which were even worse than the hills. We do not have roads a mile wide nowadays, but this was not an unheard-of thing in the days of the pioneer roads. It was preferable to have them a mile wide rather than a mile deep, which would certainly have been the case in some places if one track had been used alone. And even with numberless side tracks, skirting in every direction around the more dangerous localities, horses were not infrequently drowned, and great wagons heavy with freight sometimes sank completely out of sight. The Black Swamp Road through Ohio south of Lake Erie was one of the most important in the West. It is recorded that on one occasion six horses were able to draw a two-wheeled vehicle but fifteen miles in three days. A newspaper of August 31, 1837, affirms that “the road through the Black Swamp has been much of the season impassable. A couple of horses were lost in a mud hole last week. The bottom had fallen out. The driver was unaware of the fact. His horses plunged in and ere they could be extricated were drowned.” It is[Pg 30] comforting to think there has been some improvement in our country highways. Such accounts as this would have a tendency to influence the most skeptical.

The rivers were also great highways for emigration, particularly such streams as the Ohio which flowed west. With the building of the great canals new and more stable methods of travel were at the disposal of prospective travelers and there was an increase in the great tide of home-seekers. The smaller inland rivers were not likely so largely used by these armies of pioneers as some have thought. For instance, in a history of one of the interior counties of Ohio (which is divided by one of the best rivers in the West) is a twenty-five page description of the first immigrants, and of only one does it say: “James Oglesby was a very early settler ... and is said to have traveled up the Muskingum and Walhounding rivers in true Indian style in a canoe.” And, though the Ohio river was always a great highway to the West and Southwest, it was used less perhaps in the early days of the immigration than later. Flat and keel boats[Pg 31] cost money, and money was a scarce article. In summer the river was very low, and one party of pioneers, at least, spent one-third of the entire time of journey from Connecticut to Marietta, Ohio, in coming down the Ohio from near Pittsburg. It took half as long to come those two hundred miles by river as to come all the way from Connecticut to the Ohio in a cart drawn by oxen. Moreover, even as late as the time of the starting of a regular line of steamer packets from Pittsburg to Cincinnati (1796) the passengers were assured in an advertisement that, in addition to being provided a place to sleep and something to eat, they would have each a loophole from which to shoot! The coming of steam navigation revolutionized river travel as later it revolutionized land travel.

This series of monographs will treat of the history of America as portrayed in the evolution of its highways of war and immigration and commerce. The more important highways, both land and water, will be specifically treated with reference to the national needs which they temporarily or[Pg 32] permanently satisfied. The study of any highway for itself alone might prove of indifferent value, even though it were an Appian Way; but the story of a road, which shows clearly the rise, nature, and passing of a nation’s need for it, is of importance. It is not of national import that there was a Wilderness Road to Kentucky, but it is of utmost importance that a road through Cumberland Gap made possible the early settlement of Kentucky, in that Kentucky held the Mississippi river for the feeble colonies through days when everything in the West and the whole future of the American republic lay in a trembling balance. It is not of great importance that there was a Nemacolin’s Path across the Alleghanies; but if for a moment we can see the rough trail as the young Major Washington saw it while the vanguard of the ill-fated Fry’s army marched out of Wills Creek toward the Ohio, or if we can picture that terrible night’s march Washington made from Fort Necessity when Jumonville’s scouting party was run at last to cover by Half King’s Indians, we shall know far better than ever the true story of[Pg 33] the first campaign of the war which won America for England, and realize as never before what a brave, daring youth he was who on Indian trails learned lessons that fitted him to become a leader of half-clothed, ill-equipped armies.

The first aim of these monographs is suggestiveness; there is a vast deal of geographic-historical work to be done throughout the United States. There is no more interesting outdoor work for local students than to trace, each in his own locality, the old land and water highways, Indian trails, portage paths, pioneer roads or early county or state roads. Maps should be made showing not only the evolution of road-making in each county in the entire land, but all springs and licks of importance should be correctly located and mapped; sites of Indian villages should be marked; frontier forts and blockhouses should be platted, including the surrounding defenses, covered ways, springs or wells, and paths to and fro; traders’ huts should all be placed, ancient boundary lines marked, old hunting-grounds mapped. Those who can[Pg 34] assist students in such explorations are fast passing away. Much can be done this year that can never be done so well in all the years which will succeed.

In subsequent monographs the author will endeavor to thank such persons as have assisted him in their preparation. For the work already completed and for that yet to be done I am especially indebted to Mr. Arthur H. Clark, for encouragement and assistance; to the Hon. Rodney Metcalf Stimson, for the freedom of his splendid collection of Americana lately presented to Marietta College; and to the patient, devoted assistance and collaboration of my wife.

A. B. H.

Marietta, Ohio, July 1, 1902.

The latest explorations of the mounds erected by those first Americans, known best as the mound-building Indians, have revolutionized our conceptions of the earliest race of which we know in America. Very many notions, founded upon the authority of the earlier archæologists, seem now to be either partly or wholly incorrect. Many assumptions as to the population of this country during the mound-building era, the degree of the civilization, and the perfection of the arts, have not been substantiated by the more accurate studies which have been made in the past decade.

The most important reason why so little progress has been made in unraveling the mystery of the mounds that abound in central North America is that “the authors[Pg 38] who have written upon the subject of American archæology have proceeded upon certain assumptions which virtually closed the door against a free and unbiased investigation.”[1] Of these assumptions, the one most detrimental to the advance of the study of archæology is that which has affirmed that “mound-builders” and American Indians were two distinct races; thus all conclusions reached concerning the “mound-builders” which were founded upon the earliest knowledge we have of the American Indian were denied to archæology. But the evidence of latest explorations and investigations makes it positive that the “mound-builders” were not a race distinct and apart from the race we know as American Indians: “The links directly connecting the Indians and mound-builders are so numerous and well established that archæologists are justified in accepting the theory that they are one and the same people.”[2]

This fact having been placed beyond the realm of speculation, a great mass of[Pg 39] testimony furnished by the study of the American Indians is to be admitted in settlement of the question raised concerning the history of the mound-builders in America.

First, this testimony will be found to set aside once and for all the exaggerated statements as to the high grade of civilization reached by these first Americans. It does not appear that the mound-building Indians occupied a higher plane than that reached by the Indians as first known by Europeans. One of the most exaggerated notions of these Indians is that which ascribes to them very perfect ideas of measurement; the alleged mathematical accuracy of certain of their monumental works having been cited repeatedly as a sign of their advanced stage of civilization. It has even been affirmed that their mathematical accuracy could hardly be excelled by the most skillful engineers of our day.

Recent explorations have dispelled this entertaining theory: “The statement so often made that many of these monuments have been constructed with such mathematical accuracy as to indicate not only a[Pg 40] unit of measure, but also the use of instruments, is found upon a reëxamination to be without any basis, unless the near approach of some three or four circles and as many squares of Ohio to mathematical correctness be sufficient to warrant this opinion. As a very general and in fact almost universal rule the figures are more or less irregular, and indicate nothing higher in art than an Indian could form with his eye and by pacing.”[3]

The fanciful theory of a great teeming population during the mound-building era is equally without foundation. Even the size and extent of the mounds do not imply a great population. An authority of reputation gives figures from which it can be shown that four thousand men, each transporting an equivalent of one wagon-load of earth and stone a day, could have erected all the mounds in the state of Ohio (which contains a greater number than any other in the Union) in one generation.[4]

When it is realized that the art for which the earliest Indians have been most extolled was not, in reality, in advance of that known by the ordinary Indian, and that the population of the country in the mound-building era cannot be shown to have exceeded the population found when the first white men visited the Indian races, it is easy to see in the erection of the mounds, the burial of dead, the rude implements common to both, the poor trinkets used for ornamentation, the houses each built, the weapons each employed, a vast deal of additional testimony proving that the “Mound-builder” and Indian were of one race.

Thus the true historical method must be to compare what is definitely known of the earliest Indians with the relics and memorials which are surely those of the mound-building era in order to reach undoubted facts concerning the prehistoric Indians. This applies equally to customs, weapons, edifices, ornaments, and what is of present moment to our study: highways of travel.

However, a complete detailed study of the highways of the early Indians according[Pg 42] to this method will not be indulged in for certain respectable reasons; there are very few undoubted routes of the mound-building Indians, and a detailed comparative study of these and later Indian routes would become, under the circumstances, too speculative to be of genuine historical value. Our purpose, then, will be, merely to give the reasons for believing that the earliest Indians had great overland routes of travel; that, though they lived largely in the river valleys, their migrations were by land and not by water—in short, that these first Americans undoubtedly marked out the first highways of America used by man, as the large game animal, the buffalo, marked out the first great highways used by animal life.

These highways were the highestways because their general alignment was on the greater watersheds: and our study may be better described perhaps by a subtitle—a study in highestways.

The mounds of these first Americans of which we know are found between Oregon and the Wyoming valley, in Pennsylvania, and Onondaga county in New York; they extend from Manitoba in Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

The great seat of empire was in the drainage area of the Mississippi river; on this river and its tributaries were the heaviest mound-building populations. Few mounds are found east of the Alleghany mountains.

In the Catalogue of Prehistoric Works East of the Rocky Mountains, issued by the Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution,[5] the geographical extent and density of the mounds in central North America is brought out state by state with striking suggestiveness. While the layman is[Pg 44] warned that these maps “present some features which are calculated to mislead,” and that the maps indicate “to some extent the more thoroughly explored areas rather than the true proportion of the ancient works in the different sections,” still some conclusions have already been reached which future exploitation will never weaken.

It is not expected that future investigation will change the verdict that the heaviest mound-building population found its seat near the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. “There is little doubt,” writes Dr. Thomas, “that when Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia have been thoroughly explored many localities will be added to those indicated ... but it is not likely that the number will be found to equal those in the area drained by the Ohio and its affluents or in the immediate valley of the Mississippi.”[6]

This fact, that the heaviest populations of the mound-building Indians seem to have been near the Mississippi and Ohio is, of[Pg 45] course, shown by the archæological maps. In a rough way, subject to the limitations previously mentioned, it can be found that the following fourteen states contain evidences of having held the heaviest ancient populations:

|

Ohio, Wisconsin, Tennessee, Illinois, Florida, New York, Kentucky, Indiana, |

Michigan, Georgia and Arkansas, Missouri and North Carolina, Minnesota, Iowa, Pennsylvania. |

Now, by our last census the states which contain the largest population today are:

|

New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Texas, Missouri, Massachusetts, |

Indiana, Michigan, Iowa, Georgia, Kentucky, Wisconsin, Tennessee. |

Thus of the fourteen most thickly populated states today perhaps twelve give fair evidence of having been most thickly popu[Pg 46]lated in prehistoric times. As a general rule (but one growing less reliable every day) the heaviest population has always been found in the best agricultural regions; the states having the largest number of fertile acres have had, as a rule, the largest populations—or did have until the cities grew as they have in the past generation.

This argument, though necessarily loose, still is of interest and of some importance in the present study. The earliest Indians found, without any question, the best parts of the country they once inhabited if we can take the verdict of the present race which occupies the land.

Click here for larger image size

Archaeological Map of Wisconsin[Showing interior location of remains]

Coming down to a smaller scope of territory, can it be shown that in the case of any one state the early Indians occupied the portions most heavily populated today? It has been said that, in Ohio, four counties contain evidence of having been the scenes of special activity on the part of the earliest inhabitants: Butler, Licking, Ross, and Franklin. These are interior counties (at a distance from the Ohio and Lake Erie) and, of the remaining sixty-three interior counties in the state, only seven exceeded [Pg 49] these four in population in 1880—when the cities had not so largely robbed the country districts of their population as now. Thus the aborigines seem to have been busiest where we have been busiest in the last half of the nineteenth century.

In Wisconsin the mound-building Indians labored most in the southern part of the state, where the bulk of that state’s population is today—seventy-five per cent being found in the southern (and smaller) half of the state.

In Michigan, a line drawn from the northern coast of Green Bay to the southwestern corner of the state includes a very great proportion of the archæological remains in the state. That line today embraces on the southeast thirty-three per cent of the counties of the state, yet sixty-three per cent of the population.

Thus it can be said that in a remarkable measure the mound-building peoples found with interesting exactness the portions of this country which have been the choice spots with the race which now occupies it.

Here, in the valleys, and between them,[Pg 50] toiled their prehistoric people. Their low grade of civilization is attested by the rude implements and weapons and domiciles with which they seem to have been content. Divided, as it is practically sure they were, into numerous tribes, there must have been some commerce and there was, undoubtedly, much conflict. Above their poorly cultivated fields, or in the midst of them, they erected great earthen and stone fortresses, and, flung far and wide over valley and hill, stand the mounds in which they buried their dead.

It has been noted that a considerable portion of archæological remains in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin are inland—or away from the largest river valleys. The lands on the lesser streams were occupied in some instances for the entire distance to the springs. For instance, in Ohio and Kentucky we find only a fraction of the ancient works on the shores of the Ohio river—either mounds or forts. In Ohio the largest collections are found in the interior counties mentioned, as is the case in Kentucky, at a distance varying from fifty to one hundred and fifty miles from the great water highway which flows by these states on the north or on the south.

As with these states, so with the counties within them—the mound-building people seem to have been scattered widely. An[Pg 54] archæological map of Butler county, Ohio, shows that the remains are found everywhere quite without reference to the largest streams. In this county there are more works in Oxford township in the far corner of the county than in Hanover township, which lies between Oxford and the Miami river. Today there are six hundred more inhabitants in Oxford township (exclusive of the population of Oxford village) than in Hanover township. There are more remains in Reily township, which is separated from the Miami by Ross township, than in Madison township, which is bounded by the Miami and is drained by a larger stream than any in Reily. St. Clair township contains several works in the western portion, on the branches of the Miami river, and almost none at all in the eastern portion which is bounded by that river itself.

Crawford county, Wisconsin, has also been mapped. Though bounded on the south and west by the Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers, fifty per cent of the ancient works are at a distance from those streams.

Click here for larger image size

Archaeologic Map of Illinois and Indiana[Showing interior location of remains]

The large proportion of remains in Kentucky are in the western portion of the state situated along the watershed between the Ohio and Tennessee valleys. In Indiana the great majority of works are in the eastern tier of counties where there are no streams of importance.

This makes up a sum of testimony that enables one to say that in some instances at least the mound-building peoples were largely a rural people; in some noticeable instances their works are found more profusely on the smaller streams than on larger ones. In this they differed in no wise from the red-men who were found living in these regions mentioned when the whites first came to visit them, and we might have held to our original line of reasoning to reach this same conclusion. It might have been shown that the red-men in Ohio and some of the neighboring states lived more on the smaller streams than on the larger ones, and then made the deduction that the mound-building people did the same.

For this was true. The three centers of Indian population in Ohio were on the[Pg 58] smaller streams. The Delawares made their headquarters on the upper Muskingum; the Wyandots had their villages on the Sandusky river and bay; the Shawanese were on the Scioto, and the Miamis on the rivers that have borne their name. The well-known Indian settlements on the Ohio and on Lake Erie can almost be counted on the fingers of one hand, while the towns at Coshocton, Chillicothe, Piqua, Fremont, and Dresden were of national importance during the era of conquest. Referring to the location of the Indians of Ohio an early pioneer casually writes: “Their habitations were at the heads of the principal streams.”[7] There was almost no exception to the rule.

The explanation of this may be found partly in the great floods which were, doubtless, more menacing near the larger streams. While the floods rise perhaps faster today, it is doubtful if they reach the height that they did in earlier days. Then, at flood-tide, a thousand forest swamps, licks, pools, and lagoons which do not exist today added their waters to the river tides. General[Pg 59] Butler, who was on the lower Ohio just after the Revolution, was advised by a friendly Indian chief to locate Fort Finney high up from the Ohio in order to be clear of high water. Under the date of October 24, 1785, he wrote in his Journal: “Capt. George, who had lived below the mouth of this river [Miami] assured me that all the bank from the river for five miles did absolutely overflow, and that he had to remove to the hill at least five miles back, which determined me to take the present situation.”[8]

Under such circumstances as these it is not surprising that the Indians preferred the little rivers to the larger ones. The smaller streams amid their hills did not rise so high, and when they did rise safe camping spots could be found on high ground not far removed.

What was true of these Indians was probably true of any antecedent race.

Assuming, then, that the mound-building people lived (in these states more particularly noticed) on the lesser “inland”[Pg 60] streams where the later Indians were found, there is no question but that they moved about the country more or less as the Indians themselves did. Although the former people were more nearly a stationary people, yet we know that they hunted, and it is not reasonable to believe that they did not have commercial intercourse. In fact, from the contents of their mounds, we know they did. We also know that the various tribes made war upon one another, or at least were made war upon by some enemy.

All this necessitated highways of travel. Any one who has studied the West during Indian occupancy does not need to be asked to remember that travel in the earliest days in the interior was by land as well as by water. Those making long journeys at propitious seasons, such as the Iroquois who went southward in war parties, the Moravians being transferred to Ohio from Pennsylvania, pioneers en route down the Ohio river to Kentucky, the Wyandots on their memorable hegira to the Detroit river, used the waterways. But the main mode of travel for explorers, war parties, pioneer[Pg 61] armies and missionaries seems to have been by the paths which threaded the forests.[9]

Of the hundreds of Indian forays into Virginia and Kentucky there is perhaps not one, even those moving down the Scioto and up the Licking, that used water transportation. In their hunting trips the canoe was useless except for transporting game and peltry to the nearest posts, and this was done often on the little Indian ponies.

For long months the lesser streams were ice-bound in the winter; in the summer, for equally long periods, they must have been nearly dry, as in the present era of slack-water navigation the larger of them are frequently very low. Even travel on[Pg 62] the Ohio in low-water months was exasperatingly slow. One pilgrim to Ohio spent ninety days en route from Killingly, Connecticut, to Marietta, Ohio—thirty-one of them being spent in getting from Williamsport, Pennsylvania, down the Monongahela and Ohio to Marietta! The journey from Connecticut in a cart drawn by oxen to the Monongahela took but twice the time needed to come down the rivers to Marietta on a “Kentucky” flatboat![10] With high-water, and going down stream, a hundred miles a day could be covered.[11]

That the first pioneers into the interior of Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana preferred land routes to water is plain to the most casual reader of the history of the pioneer period. Such great entrepots as Wellsburg, Ohio, Limestone, Kentucky, and Madison, Indiana (all on the Ohio), attest the fact that the travel to the interior was by land routes and not by the smaller rivers.

And so, throughout historic times, one rule has held true in the region now under[Pg 63] survey: that the lesser streams have never been used to any large degree as routes of travel by the white race, or by the red race before them. It is thus reasonable to believe that the earliest people, who so largely inhabited the interior valleys, found land travel more sure and expeditious than water travel on the little streams. A great many mound-building people lived by these smaller streams where so many of their works now stand. That they had ways of getting about the country goes without saying. In some instances the earth and stone with which they worked was brought from a distance. This could not have been accomplished by any means by water. We know they fought great battles; it is exceedingly doubtful and all against the lesson taught in times that are historic, that these armies traveled water routes. True, there were watch “towers” along the river banks, and the rivers of real size were undoubtedly the routes of armies—but it has been the opinion of some archæologists that their enemies came from the north. There are no rivers flowing from the interior of Ohio, for instance, to Lake Erie that[Pg 64] are even now when dammed of a size sufficient to warrant us the belief that great armies passed over them.[12] We cannot imagine a hostile army of power great enough to have necessitated the building of such a work as Fort Ancient ever coming to it on the little river on which it stands.

Speaking of the mound-building Indians, MacLean remarks: “In order to warn the settlements [of mound-builders], where such a band should approach, it was found necessary to have ... signal stations. Judging by the primitive methods employed, these wars must have continued for ages. If the settlements along the two Miamis and Scioto were overrun at the same time before they had become weakened, it would have required such an army as only a civilized or semi-civilized nation could send into the field. It is plausible to assume that a predatory warfare was carried on at first, and on account of this the many fortifications were gradually built.[Pg 65] During a warfare such as this, the regular parties of miners would go to the mines, for the roads could be kept open, even should an enemy cross the well-beaten paths.”[13] Here a scholar of reputation gives the strongest kind of evidence in a belief that overland routes of travel were in existence and were employed in prehistoric times—by incidentally referring to them while discussing another question. It is difficult to think of any possible alternative. The verdict of history is all against another.

Assuming, then, that overland routes of travel were used by this earliest of American races of which we have any real knowledge, it is to the purpose of our study to consider where such routes were laid.

The one law which has governed land travel throughout history is the law of least resistance, or least elevation. “An easy trail to high ground” is a colloquial expression common in the Far West, but there has been a time when it was as common to Pennsylvania and Ohio as it is common today along the great stretches of the[Pg 66] Platte. The watersheds have been the highways and highestways of the world’s travel. The farther back we go in our history, the more conclusive does the evidence become that the first ways were the highestways. Our first roads were ridge roads and their day is not altogether past in many parts of the land. These first roads were “run,” or built, along the general alignment of the first pioneer roads, which, in turn, were nothing more than “blazed” paths of the Indian and buffalo. A single glance at one of the maps of the Central West of Revolutionary times, for instance, will show how closely the first routes clung to the heights of the watersheds. And for good reason: here the ground suffered least from erosion; here the forests were thinnest; here a pathway would be swept clear of snow in winter and of leaves in summer by the swift, clean brooms of the winds. For the Indians, too, the high lands were points of vantage both in hunting and in times of war.

In every state there were strategic heights of land, generally running westward; in Ohio, for example, the strategic watershed[Pg 67] was that between the heads of the lake rivers and the heads of those flowing southward into the Ohio. Across this divide ran the Great Trail toward Detroit and the lake country. In western Virginia a strategic watershed was that formed between the heads of streams flowing northward into the Ohio and southward into the Kanawha. And in a remarkable degree the strategic points of a century and a half ago are the strategic points today, a fact attested by the courses of the more important trunk railway lines. The steady rise and importance of such a city as Akron, Ohio, is due to a strategic situation at the junction of both an important portage path and of a great watershed highway.

With all these facts in mind it is not presumptuous then to inquire whether the mound-building Indians did not find the high lands and mark out on them these first highways of America.

In examining the standard work on the exploration of the American mounds, the Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, by Dr. Cyrus Thomas, it is plain that the mound-building Indians were well acquainted with the watersheds and high lands in the regions which they occupied. As a general rule it can be said that they cultivated the lowlands and built their forts and mounds upon the adjacent heights; but, so widespread are their works over the counties which they occupied, that it seems evident that they were at least well acquainted with all the surrounding territory. Whatever may have been the significance of their works, it is reasonable to believe that they were erected to be seen and visited; it is sane to believe that they[Pg 69] were erected near the highways traveled, as has been the case with all other races of history. It is now in point to show that their mounds and effigies were not only on high ground, but often on the ranges of hills.

Examining Crawford county, Wisconsin, we find the mound-builders’ works “on the main road from Prairie du Chien to Eastman,” which “follows chiefly the old trail along the crest of the divide between the drainage of the Kickapoo and Mississippi rivers.... The group is, in fact, a series or chain of low, small, circular tumuli extending in a nearly straight line northwest and southeast, connected together by embankments.... They are on the top of the ridge.”[14]

“About 2 miles from Eastman, ... just east of the Black River Road, ... are three effigy mounds and one long mound.... They are situated in a little strip of woods near the crest, but on the western slope of the watershed and near the head of a coulee or ravine.”[15]

“In the same section ... are the remains of two bird-shaped mounds, both on top of the watershed.”[16]

“The next group surveyed ... are on the crest of the ridge heretofore mentioned and on both sides of the Black River Road.”[17]

“Mound No. 23 ... is also in the form of a bird with outstretched wings. It lies ... on top of the ridge, with the head lying crosswise of the highest point.”[18]

“Mound No. 24 is close to the right or east, on the high part of the ridge, extending in the same direction as 23.”[19]

“Northward of this group some 400 yards, there is a mound in the form of a quadruped, probably a fox, ... partly in the woods and partly in the field on the west side of the road. It is built on the crest of the ridge with the head to the south.”[20]

“About a mile southward of Hazen Corners ... is a group.... They are all situated on the northern slope of the ridge not far from the top.”[21]

“... A small group ... situated west of the Black River Road, ... on the top of the ridge in the woods. The ridge slopes from them to the east and west.”[22]

“Some 10 or 12 miles southwest of the battle-field of Belmont [Missouri] is one of the peculiar sand ridges of this swampy region, called Pin Hook ridge. This extends 5 or 6 miles north and south, and is less than a mile in width.... There is abundant evidence here that the entire ridge was long inhabited by a somewhat agricultural people, with stationary houses, who constructed numerous and high mounds, which are now the only place of refuge for the present inhabitants and their stock from the frequent overflows of the Mississippi.”[23]

“These ... are situated on the county road from Cairo, Illinois.... They are the highest ground in that immediate section” (Missouri).[24]

Crowley’s Ridge, running through Green, Craighead, Poinsett, and St. Francis counties (Arkansas) forms the divide between the waters of White and St. Francis rivers, and terminates in Phillips county just below the city of Helena. Most of the bottom lands are overflowed during high water. There are some evidences of archæological remains throughout the length of this ridge.[25]

“The works ... one mile northeast of Dublin [Franklin county, Ohio] ... are on a nearly level area of the higher lands of the section.”[26]

“The group shown ... is on a high hill near the Arnheim pike, Brown county [Ohio].”[27]

“On nearly every prominent hill in the[Pg 73] neighborhood of Ripley [Brown county, Ohio] are stone graves.”[28]

“Just east of Col. Metham’s residence, on a high point overlooking the valley ... was a mound.”[29]

“... A group ... located 2 miles southwest of the village of Brownsville [Licking county, Ohio] and half a mile south of the National Road, on a high hill, from which the surrounding country is in view for several miles.”[30]

In the Catalogue of Prehistoric Works issued by the Bureau of Ethnology almost every page gives proof that the mound-builders were occupants of the highlands. Some quotations will be in place:

“Inclosures, hut-rings, and mounds on a sandy ridge between the Mississippi River and Old Town Lake at the point where they make their nearest approach to each other, and near the ancient outlet of Old Town Lake” (Phillips county, Arkansas).[31]

“... Remains of an Indian fort on the summit of a precipitous ridge near Lake Simcoe.”[32]

“Stone cairn ... on ridge between Anawaka and Sweetwater creeks” (Douglass county, Georgia).[33]

“Stone cairn on a ridge” (Habersham county, Georgia).[34]

“Stone mound on a ridge” (Hancock county, Georgia).[35]

“Deposit ... on a ridge half a mile south of Clear Creek” (Cass county, Illinois).[36]

“Mounds on the spur of a ridge, midway between the Welsh group [Brown county] and Chambersburg, in the extreme northeastern part of the county” (Pike county, Illinois).[37]

“Group of mounds on a ridge in Skillet Fork bottom” (Wayne county, Illinois).[38]

“Mounds on several high hills” (Franklin county, Indiana).[39]

“Four mounds on top of a ridge near Sparksville” (Jackson county, Indiana).[40]

“Stone enclosure known as Fort Ridge” (Caldwell county, Kentucky).[41]

“Indian mounds ... on ‘Indian Hill’” (Hancock county, Kentucky).[42]

“A group of circular mounds scattered along a ridge between Fox river and Sugar Creek” (Clark county, Missouri).[43]

“Two parallel embankments stretching across a hog-back between two ravines” (Livingston county, New York).[44]

“Embankments on Ridge road ... along the edge of the bluff overlooking the Ridge road” (Niagara county, New York).[45]

“Cairns on ridges” (Caldwell county, North Carolina).[46]

“Stone cairns ... on trail crossing ridge between Tuckasegee river and Alarka Creek” (Swain county, North Carolina).[47]

Flint Ridge in Coshocton and Licking counties, Ohio, contained stone and earth mounds and quarries; “Indian trail from Grave Creek mound, West Virginia, to the lakes, passing over Flint Ridge.”[48]

Some of these remains are undoubtedly of no later age than the Indians whom the first whites knew; many of them are of far earlier times. It is now held by the most prominent archæologists that there are works of the mound-building Indians which do not date back far from the time Columbus discovered America. Thus any work which gives evidence of having been in existence five hundred years may belong to the mound-building era. And throughout all these five hundred years there is hardly a time when there is not evidence of Indian occupation. So the line between the mound-building Indians and the later [Pg 79] Indians, among whom the building of mounds was a lost art, is exceedingly hard to draw.

These quotations give some evidence that the builders of our earliest archæological works were well acquainted with the high grounds. It is not apparent now that in any signal instance there exists evidence of a reliable character that any watershed was a highway; all we are seeking to show now is the very general fact that these people lived and moved and had their being often far inland on the heads of the little streams which never in historic times have served the purpose of navigation, and that here many of their works are found on the high grounds where it is sure all previous races have made their roads.

Now, it has been suggested already that lines of land travel have varied little since the time the buffalo and Indian marked out the best general courses across the continent. Mr. Benton said that the buffalo blazed the way for the railroad to the Pacific. In a general way this has been the rule throughout our history; the first routes chosen have often proved the best the tripod[Pg 80] could find. Now it would be significant if it could be proved that there are numerous archæological remains along these strategic lines of travel. This, probably, cannot be shown. There is, however, strong evidence that is worthy of consideration. Many of the early routes of travel converged on certain well-worn, strategic gaps in our mountain ranges. It is interesting to notice how many archæological remains are found at these points. A few quotations from the Catalogue of Prehistoric Works will be in point:

“Stone cairns in Rabun Gap” (Rabun county, Georgia).[49]

“Pictographs on large bowlders in Track Rock Gap” (Union county, Georgia).[50]

“Ancient fire-bed and refuse heap at Buffalo Gap (bones and pottery found here)” (Union county, Illinois).[51]

“Mound near Cumberland Gap” (Bell county, Kentucky).[52]

“Cairn at Indian Grave Gap on Green Mountain ... in the trail” (Caldwell county, North Carolina).[53]

“Mound ... said to be ... toward Grandmother Gap” (Caldwell county, North Carolina).[54]

“Mound ... one mile southwest of Paint Gap post-office.... Cairn at Indian Grave Gap, in Walnut Mountain ... on south side of road from Marshall to Burnsville” (Madison county, North Carolina).[55]

“Cairn at Boone’s Gap on Boone’s Fork of Warriors Creek” (Wilkes county, North Carolina).[56]

“Cairns at Indian Grave Gap” (Blount county, Tennessee).[57]

“Cairns in the gap on the state line at Slick Rock trail” (Monroe county, Tennessee).[58]

“Mound 500 feet long, 250 feet wide, and 40 feet high ... 2¼ miles west of Rockfish Gap Tunnel” (Augusta county, Virginia).[59]

Some of these cairns do not, in all probability, date back to the mound-building era, but the mounds and other archæological works probably do, giving the best reasons for believing that the earliest of Americans found the strategic paths of least resistance across our great divides.

But not only in the mountain passes have our tripods placed their stern stamp of approval upon the ingenuity of the earliest pathfinders of America. In a host of instances our highways and railroads follow for many miles the general line of the routes of the buffalo and Indian on the high ground. This is particularly true of our roads of secondary importance, county roads, which in hundreds of instances follow the alignment of a pioneer road which was laid out on an Indian trail.

No one can examine the maps and diagrams of the archæological works of central North America with this truth in mind[Pg 83] without noticing how largely these works are found near to some present-day thoroughfare. This is of significance. While it is true that works near such highways are perhaps more quickly discovered and easily approached, it is at the same time doubtful if any of importance have been ignored because they are at a distance from highways of approach. The relation of these works to neighboring roads has also been accidentally emphasized by the necessity of describing their position, which is often most easily done by a reference to adjacent roads. For all this due allowance must be made. At the same time this does not explain the fact that a significant fraction of these works lie along the general alignment of our present routes of travel and are in numerous instances touched by them. It need hardly be added that these roads were laid out with as much reference to the stars above them as to the ancient works near which they accidentally pass.

The following instances have a bearing on the question:

Two miles from Madison, Wisconsin, a line of mounds is found beside a highway[Pg 84] to the city. The road passes through one of the group and the remainder follow the road on high ground almost parallel with it.[60]

The road from Prairie du Chien (Wisconsin) to Eastman is paralleled by a long line of works. As previously noted (p. 69) this road follows the alignment of an old Indian trail.[61]

There are mounds on both sides of the Black River road near Hazen Corners, Wisconsin.[62]

In the archæological map of Hazen Corners, Wisconsin, the works bear a significant relation to the junction of the three roads which meet there. Supposing the roads to be the prehistoric route of travel, it is seen that all the mounds lie just beside them, many even touching them, but in only one instance does a mound cross any of the three present roads. True, the roads may have destroyed some of the works, but of the effigy mounds, at least,[Pg 85] it is sure that the figures are complete, or nearly so.[63]

It is to be noticed with reference to the effigy mounds that, to a person standing on the present highway the figures are “right side up.” In the case of the animal figures, if the road runs to the left of a figure that figure is found to be lying on its right side; if the road runs on the right the figure is found to be lying on its left side; the feet are toward the road. In the case of birds, either the head or the tail is toward the present highway.[64]

A line of mounds lies on high ground on the northeast bank of the Mississippi river, near Battle Island, Vernon county, Wisconsin. The road to De Soto is on the same bank and lies parallel with them throughout their length.[65]

A remarkable line of mounds and effigies lies near Cassville, Grant county, Wisconsin. A road runs exactly parallel with them. The mounds lie on the west and the effigies[Pg 86] on the east. The animals lie in a correct position to be viewed from the road.[66]

Between the Round Pond mounds (Union county, Illinois), which are so near together that “one appears partially to overlap the other,” runs a roadway.[67]

A roadway cuts through the ancient works on the Boulware place, Clark county, Missouri; the alignment of the road and the series of works is nearly the same.[68]

The Rich Woods works, Stoddard county, Missouri, lie on a long, sandy ridge; “the general course is almost directly north and south.” The road to Dexter runs near them, touching one, in the same north and south direction the entire length.[69]

The Knapp mounds, Pulaski county, Arkansas, “the most interesting group in the state,” are surrounded by a wall of earth. A roadway passes through the entire semicircle formed by this surrounding wall,[Pg 87] and passes between or at the base of the mounds contained within it.[70]

A road runs through the entire length of the ancient stone work near Bourneville, Ross county, Ohio.[71]

A state road (Lebanon to Chillicothe) crosses over Fort Ancient. At the spot where this road ascends to the fort, the embankments of the latter are found to be increased in height and solidity, showing that this point was most easy of ascent—probably the very spot where the ancient road was made.[72]

A road passes through the entire length of the North Fork works (Ross county, Ohio).[73]

A road passes through the entire length of ancient work, Ross county, Ohio.[74]

Two roads cut ancient work in Fayette county, Kentucky.[75]

Ancient work is cut in two by road from Chillicothe to Richmondale, Liberty township, Ross county, Ohio.[76]

The state road passes through the great Graded Way in Pike county, Ohio, one of the most famous works in the United States. It is surely significant that a modern road should pass so near the very track which evidently was a highway in prehistoric times.[77]

Such are the conspicuous examples of ancient works that are now found to be on the alignment of modern routes of travel. In two singularly significant instances—in the Graded Way in Pike county, Ohio, and at Fort Ancient, Warren county, Ohio—there is no doubt that the modern road passes over the very track of the road used by the mound-builders. These two famous works, with the exception of the Serpent Mound probably the most famous in all the Central West, are near no stream of water which is not frozen in the winter and nearly dry in the summer. There can be[Pg 89] no reasonable doubt that their builders used the routes on the watersheds.

As was said at the beginning, it does not seem wise to attempt to speculate on the probable routes by which these early tribes found their way to and fro between their works within the interior of the country. That they did so pass it seems difficult to doubt. That those early ways were along the watersheds, higher or lower, we may well believe, since for the races that have occupied the land since their time these watersheds have been the routes of travel—and will be until aërial navigation is assured.

That these earliest Americans had roads of one description or another, there is sufficient evidence. About their great works there were graded ways of ascent, up which the materials used in construction were hauled or borne. Now and then we find mention of some sort of roads which may seem to have been of a less local nature, but so far as highways of war and commerce are concerned there is no evidence which can be admitted into this treatise.

It will not be of disadvantage, however,[Pg 90] to give a brief catalogue of such roads and ways as seem of most importance in the Catalogue of Prehistoric Works previously quoted:

Manitoba, Dominion of Canada: “Calf Mountain” (Tête de Bœuf), a mound 95 feet in diameter and 15 feet high, with a graded roadway 2 feet high, running southwest from it 154 feet; about 60 miles north of Pembina.[78]

Jefferson County, Georgia: Remains of large cemeteries and a broad trail leading to Old Town, 8 miles from Louisville, on the eastern side of the Ogeechee.[79]

Lowndes County, Georgia: Ruins of an “old town” within a few miles of Troupville, “with roads discernible, which are wide and straight.”[80]

Fayette County, Indiana: Camping grounds and traces of old trails in Secs. 34 and 36, T. 13 N., R. 13 E.[81]

Franklin County, Indiana: Traces of camp sites and old trails are observable on[Pg 91] Sec. 31, T. 10 N., R. 1 W.; Sec. 33, T. 10 N., R. 2 W.; Sec. 10, T. 12 N., R. 13 E.[82]

Union County, Indiana: Traces of camp sites and old trails are observable on Secs. 8 and 11, T. 11 N., R. 2 W.; Secs. 34 and 36, T. 13 N., R. 13 E.; and Sec. 7, T. 14 N., R. 14 E.[83]

Madison County, Louisiana: Group of earthworks, consisting of seven large and regular mounds and an elevated roadway, half a mile in length, on the right bank of Walnut Bayou, 7 miles from the Mississippi river.[84]

Baltimore County, Massachusetts: Old Indian trail in same county, leading from the rocks of Deer Creek (Hartford county) to an ancient settlement near Sweet Air.[85]

Licking County, Ohio: Work on Colton’s place on Newark and Flint Ridge road—a conical hill which has had a roadway “cut entirely around it; the dirt is thrown up the hill, leaving a level track[Pg 92] with a wall on the upper side.” Two miles and a half northeast of Amsterdam.

West Virginia: Indian trail from Grave Creek mound to the lakes, passing over Flint Ridge.[86]

Pike County, Ohio: Ancient works at Piketon, consisting of parallel walls, graded way and mounds.[87]

It is not, however, on this slight evidence of local roadways that one would wish to base belief that the early Indians opened the first land highways in America. It is possible that they had great, graded roads near their towns and no roads elsewhere, but it is hardly conceivable.

We have seen that the mound-building Indians occupied, in many instances, the heads of the lesser streams, and the argument in favor of their having opened the[Pg 93] first land highways has been based on this interior situation which, unless the lesson of history in this case tends to false reasoning, necessitated landward routes of travel.

There is, fortunately, one last piece of evidence which will more than make up for any lack of conclusiveness which may be laid to the charge of the preceding arguments.

A few descriptions of the local roadways of the mound-building Indians have been cited; reasons for believing that they used the watersheds, to a greater or less degree, as highways for passage from one part of the country to another, have been described. Let us look at the matter of their migrations.

That these people did migrate there is no doubt among archæologists. The many kinds of archælogical remains now found indicate that they were divided into many different tribes, and the great distances between works of similar character show that the various tribes labored at divers times in divers places. “The longest stretch where those apparently the works of one people are found on one bank [of the Mississippi river] is from Dubuque, Iowa, to the mouth of Des Moines river. As we[Pg 95] move up and down [the Mississippi] we find repeated changes from one type to another.”[88]

The direction from which these mound-builders entered the regions where their works are found, and their migrations within this region, must be decided by a careful study of the varying character of the mounds and a classification of them.

This work has not been done, save in the most general way possible, though one highly important conclusion has been definitely reached. It is that the generally received opinion heretofore held by archæologists that the lines of migration were along the principal water-courses is not found to be correct, and that these lines of migration were across the larger water-courses, such as the Mississippi, rather than up and down them.[89]

“One somewhat singular feature is found in the lines of former occupancy indicated by the archæological remains. The chief one is that reaching from New York[Pg 96] through Ohio along the Ohio river and onward in the same direction to the northeastern corner of Texas; another follows the Mississippi river; another extends from the region of the Wabash to the headwaters of the Savannah river, and another across southern Michigan and southern Wisconsin. The inference, however, which might be drawn from this fact—that these lines indicate routes of migration—is not to be taken for granted. It is shown by the explorations of the Bureau, and a careful study of the different types of mounds and other works, that the generally received opinion that the lines of migration of the authors of these works were always along the principal water-courses, cannot be accepted as entirely correct. Although the banks of the Mississippi are lined with prehistoric monuments from Lake Pepin to the mouth of Red river, showing that this was a favorite section for the ancient inhabitants, the study of these remains does not give support to the theory that this great water highway was a line of migration during the mound-building period, except for short distances. It was, no doubt, a[Pg 97] highway for traffic and war parties, but the movements of tribes were across it rather than up and down it. This is not asserted as a mere theory or simple deduction, but as a fact proved by the mounds themselves, whatever may be the theory in regard to their origin or uses.”[90]

It is for future scholarship to point out to us the origin, movements, and destiny of this earliest race after a careful comparative study of the remains which contain all we know of them. But may we not believe that the great watersheds were to them what they have been for every other race which has occupied this land? We submit: the greater watersheds should be carefully considered in connection with the study and classification of the various kinds of prehistoric remains with a view to solving the question of the movements of the mound-building Indians in America. The purpose of the first part of this monograph has been accomplished by pointing out some reasons for the belief that these early people opened the first landward passage[Pg 98]-ways of the continent on these watersheds. These may be summed up as follows:

(1). The mound-building Indians, like the later Indians, were partial to interior locations; some of their greatest forts and most remarkable mounds are found beside our smaller streams.

(2). These works are scattered widely over such regions; if there was any communication it must have been on the watersheds, land travel here always having been most expeditious and practicable through all historic times.

(3). They were acquainted with some of our most famous mountain passes, showing that they were not ignorant of the law of least resistance; and, to a marked degree, their works are found beside, and in general alignment with, our modern roads—which to a great degree followed the ancient routes of the Indians which so invariably obeyed this law.

(4). The comparative study of the mound-building Indians’ works proves that the migrations of that race did not follow even the larger streams by which they labored most extensively.

When the first Europeans visited the Central West two sorts of land thoroughfares were found by which the forests could be threaded: paths of the aborigines and paths of the great game animals such as the buffalo. These paths were familiarly known for half a century as Indian Roads and Buffalo Roads. That these two kinds of thoroughfares were easily distinguishable one from the other and that both were ways of common passage through the land will be made plain later.

Many varying theories regarding the coming of the buffalo into the central and eastern portions of this continent have been devised, but of one thing we are sure, namely that, among all the relics exhumed from the mounds of the pre-Columbian[Pg 102] mound-building Indians, very few bones of the buffalo have been found. Bones of other animals are frequently, even commonly, brought to light, but the remarkable fact remains that almost no buffalo bones are discovered. Considering that the buffalo was the most useful animal possible to aboriginal tribes like those in prehistoric America, there is but one conclusion to be reached, and that is that the mound-building Indians had but little acquaintance with the buffalo.

For this reason it has seemed altogether best to treat the routes of the mound-building Indians first, and the routes of the great game animals, which were known as Buffalo Roads, second—on the theory that the buffalo came into the Central West sometime between the mound-building era and the arrival of the first European explorers.[91]

The range of the buffalo or bison in the United States formerly extended from Great Slave Lake on the north to the northeastern provinces of Mexico on the south—from 62° latitude to 25°. Its westward range extended beyond the Rocky mountains and embraced quite a large area, remains having recently been discovered as far west as the Blue mountains in Oregon; farther south, herds roamed over the region occupied by the Great Salt Lake basin and grazed westward as far as the Sierra Nevada mountains. East of the Rocky mountains the feeding-grounds embraced all the area drained by the Ohio river and its tributaries, extending southward beyond the Rio Grande and northward to the Great Lakes as far as the eastern extremity of Lake Erie. The southeastern range probably did not extend beyond the Tennessee[Pg 104] river, and only in the upper portions of North and South Carolina did it extend beyond the Alleghanies.

The habitat of the buffalo included feeding-grounds, stamping-grounds, wallows and licks. Their feeding-grounds embraced the meadow valleys where the choicest grazing was to be found.[92] The habit of keeping together in immense herds while feeding soon exhausted the food in any single locality and rendered a slow, constant movement necessary. A herd so immense that it remained in the sight of a traveler for days required a vast area of feeding-ground to sustain it during a season.

When a herd rested to ruminate the buffaloes arranged themselves in a peculiar, characteristic manner—the young always in the center with the mothers, the males forming a compact circle around them. By such a conformation were the “stamping-grounds” made—each animal crowding and pushing from the outside of the herd, where flies and insects were more troublesome, toward the center.

A peculiar custom of the buffalo was “wallowing.” In the pools of water the old fathers of the herd lowered themselves on one knee, and with the aid of their horns, soon had an excavation into which the water trickled, forming a cool, muddy bath. From his ablutions each arose, coated with mud, allowing the patient successor to take his turn. Each entered the “wallow,” threw himself flat upon his back, and, by means of his feet and horns, violently forced himself around until he was completely immersed. After many buffaloes had thus immersed themselves and, by adhesion, had carried away each his share of the sticky mass, a hole two feet deep and often twenty feet in diameter was left, and, even to this day, marks the spot of a buffalo wallow. The “delectable laver of mud” soon dried upon the buffalo and left him encased in an impenetrable armor secure from the attacks of insects.

While the actions of a herd of buffaloes were very similar to those of a herd of cattle, yet very dissimilar to the habit of domestic cattle was their propensity to roll upon the ground. Though a bulky, ungraceful[Pg 106] animal in appearance, the buffalo rolled himself completely over, apparently with more ease than a horse. A buffalo, by rolling over in this manner, often dusted himself in what was known as a “dry wallow.”

The buffaloes’ licks, which afforded salt, that mineral so necessary to their health, were the foci of all their roads, the favorite spots about which the herds gyrated and between which they were continually passing. So important were these considered when white men first entered the West that every lick was carefully included in all the maps of the first geographers. Filson’s map of Kentucky, for instance, made during the Revolutionary period, contains a large number of circles with dots about them which were the signs of “Salt Springs & Licks,” all of them being connected, by trails, “some cleared, others not.”

The saline materials of these licks are derived from imprisoned sea-water which has been stored away in the strata below the action of surface waters. When these rocks lie nearer the surface than the line of drainage, the saline materials are leached[Pg 107] away. The saline materials increase with the depth until the level is reached where we find the water saturated with the ingredients of old sea-water. The displacement of these imprisoned waters is induced by the sinking of surface water through the vertical interstices of soil and rock, and the natural tendency of the water to restore the hydrostatic balance. This action is much more likely to occur when the rocks above the drainage are limestone or shale with an underlying bed of rock composed of sandstone or other rock through which water may permeate. That such a pressure exists and that some such process is at work is shown by the waters rising ten feet or more above the surface when enclosed in a pipe.